Dr Caroline Webb, Dr Stephen Jeffares, and Dr Tarsem Singh Cooner

Does local government need a devolved AI service to help the sector successfully harness the transformative power of AI? A new paper from the Tony Blair Institute (TBI) thinks so.

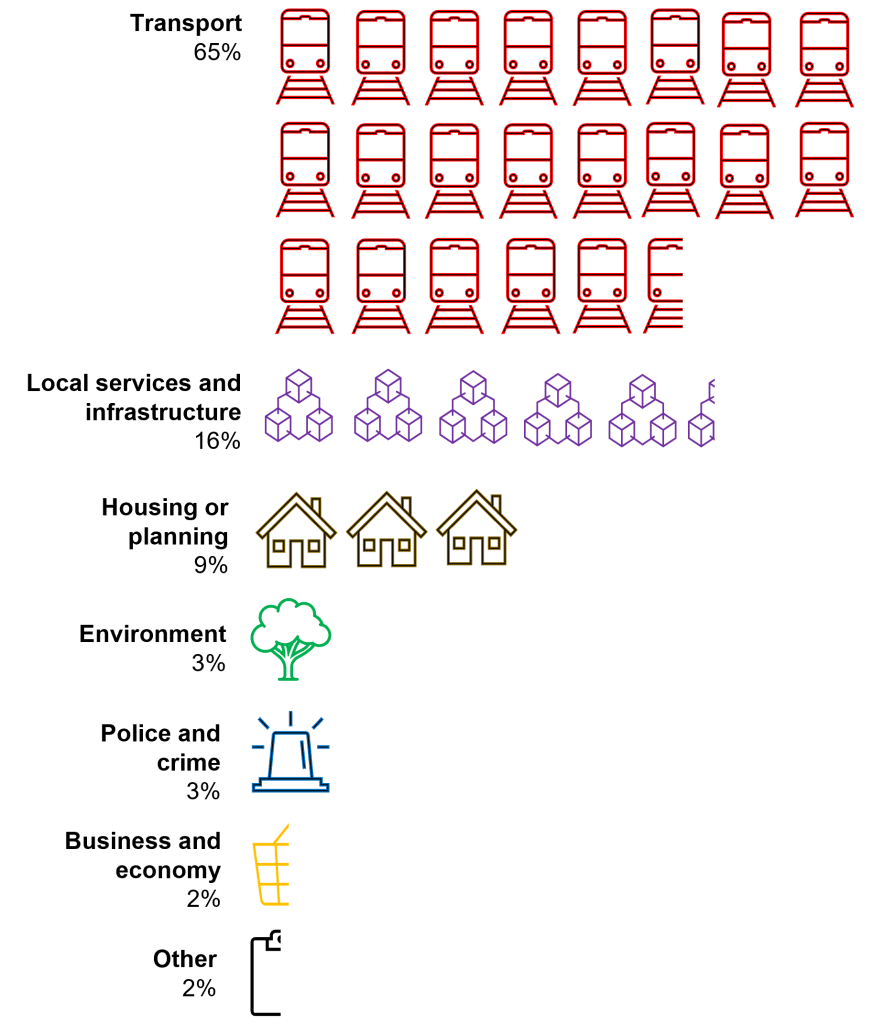

In their recent report “Governing in the Age of AI: Reimagining Local government” TBI make the case that local government faces several significant challenges – there’s a growing backlog of people seeking support coupled withdwindling resources and two thirds of funds must be spent on social care. Satisfaction is declining. Over £1.8bn is spent by the sector on technology, but innovation is stifled by a patchwork of legacy systems. The solution TBI suggest is the universal embracing of AI tools, but which is orchestrated, curated, supported and (one day perhaps) exploited via the establishment of a Devolved AI Service (DIAS).

The adoption of AI by councils continues to accelerate. Vendors of these tools extol the positive outcomes of AI, suggesting that “the day-to-day tasks of local government, whether related to the delivery of public services or planning for the local area, can all be performed faster, better and cheaper with the use of AI” (p3). The UK, they argue, could save £200 billion over five-years though AI related productivity improvements (p7).

Whilst AI undoubtedly has the potential to increase the efficiency of some public services, we must pause to ask is it really the panacea that it is being marketed as, and are some public services being unfairly targeted by technology firms looking to promote their products and capitalise on an emerging market?

There is a clamour in the social care sector for example, which accounts for 64.8 per cent of the total budget for local government in England, to develop AI tools that can offer significant time savings, with the rationale that workers can spend more quality time with clients and less time on completing paperwork. TBI cite Beam’s automated note-taking tool Magic Notes, that aims to transform social workers’ productivity by saving them s up to ‘a day per week on admin tasks’. Yet without external scrutiny and verifiable evaluation, such figures are little more than marketing claims.

As these technologies are capturing and summarising meetings to support some of the most vulnerable members of society, there is a need for local councils to interrogate these marketing claims critically before committing to such AI tools. Despite safeguards such as ensuring a ‘human in the loop’, if these claims are not thoroughly examined there is a danger that these technologies may serve to reinforce and perpetuate existing biases, pose risks to clients’ data privacy and safety, strengthen process-driven systems which undermine person-centred decision making, and erode the relational foundations on which these services are built.

Of course, AI has numerous applications beyond reducing the cost of resource intensive casework. It has the potential to address some of the most despised and most intractable local policy problems (potholes, mould, chronic pain, mental health waiting lists). But the desirability of these innovations should not cause us to forget that these technologies themselves are not neutral, and just as they can lead to positive outcomes, if they are misused or implemented without proper ethical considerations, then adverse effects are just as likely to emerge.

The proposed introduction of a Devolved AI Service may go some way to ensuring a set of standardised safeguards, allowing for a coordinated approach to AI adoption within public services. This collective approach could reduce duplication, provide practical support for the implementation and evaluation of sector-specific AI tools and facilitate a collaborative approach to working with technology providers to improve their products. However, is it necessary to impose another central regulator on Local Government? There is already considerable piloting and evaluation of AI tools being conducted at the local level. These sector-specific evaluations are facilitating opportunities for shared horizontal learning across organisations. But it is vital that these results are shared, and that the evaluative measures and methods being employed are not imposed by the vendor of the tool, but rather determined by the needs of the organisation and the people they serve. Such evaluation should also consider more than value for money or accuracy, but also the experiences of frontline staff and citizens.

Ultimately, irrespective of how we chose to oversee the integration of AI tools, we must not lose sight of the fact that these tools should only be viewed as ‘part’ of the solution to providing effective public services, not the ‘whole’ answer as some technology companies may lead us to believe.

Dr Caroline Webb, Dr Stephen Jeffares, and Dr Tarsem Singh Cooner are academics at the University of Birmingham exploring how AI is reshaping frontline public service. Combining expertise in social work, public policy, and digital ethics, they develop training and research that support practitioners to engage critically and confidently with emerging technologies. Their work champions ethical, human-centred innovation in public services.