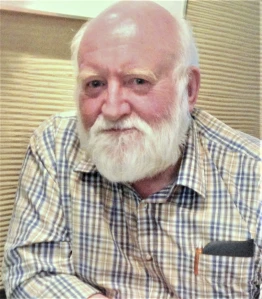

Jason Lowther

In July, then Local Government Minister Jim McMahon announced a new Local Government Outcomes Framework (LGOF), which (he said) “forms an integral part of this Government’s reforms to ensure we have a sector which is fit, legal and decent”. These reforms are already pretty extensive, including LG reorganisation, devolution, community engagement, member standards and funding arrangements.

The LGOF framework, the Minister hoped, “will help to put the right checks and balances in place to ensure value for the taxpayer and results for citizens to whom councils are ultimately responsible”. Given the removal of most systematic monitoring of local performance and outcomes in England with the demise of the Audit Commission a decade ago, is this a new dawn for helpful local insights and intelligent central steering, or the raw material for a crude league table that obscures more than it illuminates?

History shows the difficulty of designing and using performance measures effectively. Whilst the logic of measuring what matters to inform management (and political) decision making is clear, and there are many examples of successful applications, there are enough examples of failures and unintended negative consequences to encourage caution.

The immediate precursor to LGOF was a set of measures developed by the ill-fated Office of Local Government (OFLOG). These were immediately manipulated by the Times newspaper into a league table, labelling Nottingham as the worst council. The fact that this took place during the pre-election period only made the impact more negative, leading to a stinging letter from the LGA to the then Secretary of State, Michael Gove. OFLOG was in some ways set up to fail. Sited inside the Ministry, its political independence was immediately open to challenge. And reconciling providing local authorities with better data at the same time as acting as an accountability mechanism to central government was always going to be tricky.

The health service experience of performance measures and targets presents mixed evidence. It appears that four-hour A&E waiting times targets were associated with reduced mortality, but at the same time there were examples of departments admitting patients near to the time limit at the expense of others more in need of urgent care, a few examples of blatant misrepresentation of figures, and some bizarre holding of patients in ambulances and redefinition of corridors as wards.

Key lessons from these examples include the importance of having a clear focus for the LGOF and the adoption of a broad ‘exploratory’ approach to presenting the performance measures. As the Institute for Government argued for OFLOG, a key contribution could be making data more consistently available, comparable and usable – and hence supporting evidence-based policy making through the deliberative use of robust evidence.

The LGOF data needs to be presented in ways that enable and encourage exploration and questioning, rather than simplistic league tables which ignore the inherent differences between different councils in terms of population, geography, deprivation, funding, etc. It therefore needs exhibit what I call the three Cs: to be comparable across councils, contextualised to reflect local circumstances, and citizen-focussed (accessible to lay people).

There are many positive features of the new framework, including its attempt to look at missions and outcomes (rather than just council outputs). Interested parties had until 12 September 2025 to respond to the Government’s consultation, so we now await the government’s response to that. Councils can easily see how the proposed LGOF measures look for them using the excellent new LG Inform LGOF report.

Dr Jason Lowther is Director of the Institute of Local Government Studies (INLOGOV) at the University of Birmingham. This article was initially published in the Local Area Research and Intelligence Association (LARIA) newsletter. Email [email protected]