Alison Gardner & Vivien Lowndes

Anyone following the news over the last nine months might be forgiven for thinking that the UK’s relationship with austerity had taken a rollercoaster ride. In June 2015, George Osborne told central government departments to plan for 25-40% spending cuts, citing his aim for the UK to become ‘a country that lives within its means’. His ‘fiscal charter’ signalled a departure from a historic reliance on government borrowing financed through economic growth, towards an aspiration to consistently deliver a budget surplus from 2019-20 onwards. Then in the 2015 autumn statement and Comprehensive Spending Review, forecast cuts to many departments were mitigated, prompting parts of the press to herald an ‘end to austerity’. Nonetheless Osborne has since been keen to emphasise ongoing threats within the global economy, arguing that austerity remains a necessity.

From the point of view of English local authorities, continuing austerity – including a reduction in central grant funding of 60% – has been balanced against a ‘devolution revolution’: a promise of increased powers and fiscal autonomy for councils that are prepared to join together to create ‘combined authorities’ reflecting ‘functional economic geography’. For some local government advocates, devolution represents a long-sought opportunity for the sector to break free from Whitehall’s straightjacket of fiscal control. However, from a critical perspective, devolution may also represent a diversion: a convenient sleight of hand that allows the government to disavow responsibility for underfunded local services, whilst breaking Labour’s urban power base in the cities, and increasing central leverage over core areas of policy.

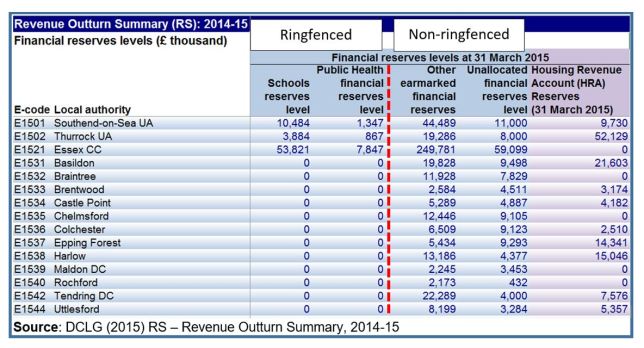

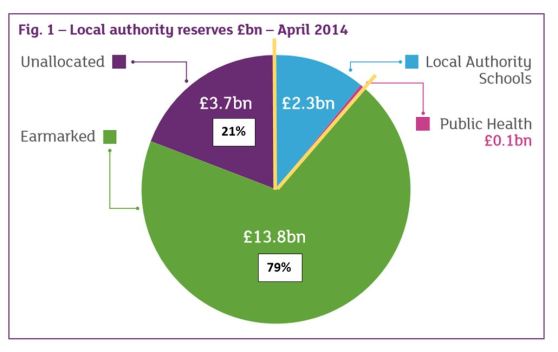

Our new article ‘Local Governance under the Conservatives: Super Austerity, Devolution and the Smarter State’ argues that – despite reports of a ‘flat’ comprehensive spending review funding settlement – local government is in fact entering a period of super-austerity, underpinned by a consistent trajectory towards reducing the size of the local state. Cuts, such as the recently announced 6.7% real terms reduction in spending power, are downplayed or obfuscated, while assumptions of growth in local sources of income will be realised unequally. Under the Coalition government , spending cuts impacted most severely upon the poorest localities, and (despite recent changes to the DCLG grant funding formula) future funding reductions – as well as unequal opportunities to raise income – threaten to reinforce a distinctive geography of austerity with deepening spatial inequalities.

Optimists point to the opportunities of devolution, reform and efficiency. Devolution has gathered cross-party parliamentary support, and large cities such as Manchester have been keen to be at the forefront of governance innovations such as combined authorities, and devolved health spending. Proposals to localise business rates, and allow (limited) flexibility to elected mayors in increasing council tax have also been welcomed. However, the economic benefits arising from devolution are uncertain and disputed, playing out unevenly and over the longer term, whilst spending cuts are front-loaded. ‘Devolution’ also effectively provides for some key functions – such as economic development – to be centralised from local government to a new sub-regional level.

In addition, rather than emerging organically as a symbol of local confidence, devolution has in recent months been focussed on strategies to mitigate local deficits, driven forward under conditions of compromise and constraint. Progress on creating combined authorities, initiated cautiously under the 2010-2015 Coalition, was rapidly accelerated by a Treasury invitation for all local authorities to submit ‘fiscally neutral’ devolution proposals in advance of the comprehensive spending review. The summer of 2015 saw an unseemly scramble to submit hastily negotiated proposals, with some awkward alliances constructed under the threat of further spending cuts. The Government has also insisted on directly elected mayors as a cornerstone to devolution deals, despite a rejection of the principle across many English cities in 2012, in a move that could potentially short-circuit existing local political structures, and diminish local democratic representation.

In relation to the wider public sector, David Cameron has outlined a vision for a “smarter state”, but proposals appear to rehash new public management principles, with relatively little focus on local government. Most local authorities are already well advanced in implementing the reforms which the government describes, and multiple studies suggest that local authorities are reaching the limits of ‘efficiencies’. Increasingly local communities are being called upon to construct their own safety nets.

In effect, the direction of local governance under the Conservatives appears to point towards a form of ‘roll-out’ neo-liberalism, signalling an active construction of an alternative and right wing model of the local state, in contrast to the deconstructive ‘roll back’ neoliberalism practiced by the Coalition. Whilst this brave new world will create opportunities – especially for areas that are already prospering – prospects are less certain for areas without strong local economies. This radical transformation also implies a technocratic transfer of power, taking place with minimal public engagement.

Dr Alison Gardner and Professor Vivien Lowndes have just published Local governance under the Conservatives: super-austerity, devolution and the ‘smarter state’ in Local Government Studies. You can get free access to the paper through the virtual special issue on local authority budgeting.

Alison Gardner has recently completed a PhD at the University of Nottingham. Her research interests include local responses to austerity, and the changing relationship between civil society and the local state. She previously worked in policy roles with local authorities, the IDeA, Local Government Association and the civil service.

Vivien Lowndes is Professor of Public Policy at the Institute of Local Government Studies, University of Birmingham UK. She has been researching institutional change in local governance for 25 years, including recently Why Institutions Matter (Palgrave 2013). Current work looks at gender and institutional change and the impacts of migration.