Carola van Eijk, Trui Steen & Bram Verschuere

In local communities, citizens are more and more involved in the production of public services. To list just a few examples: citizens take care of relatives or friends through informal care, parents help organizing activities at their children’s school, and neighbours help promoting safety and liveability in their community. In all these instances, citizens complement the activities performed by public professionals like nurses, teachers, neighbourhood workers and police officers; this makes it a ‘co-productive’ effort. But why do people want to co-produce? In our recently published article in Local Government Studies we try to answer that question by focusing on one specific case: local community safety. One of the main conclusions is that citizens have different incentives to co-produce public services, and local governments need to be aware of that.

Simultaneous to the international trend to emphasize citizens’ responsibilities in the delivery of public services, there are also concerns about the potential of co-production to increase the quality and democratization of public service delivery. One important question pertains to who is included and excluded in co-production processes. Not all stakeholders might be willing or feel capable to participate. So, acknowledging the added value of citizens’ efforts and the societal need to increase the potential benefits of co-production, it is important to better understand the motivations and incentives of citizens to co-produce public services. A better insight not only can help local governments to keep those citizens who are already involved motivated, but also to find the right incentives to inspire others to get involved. Yet, despite this relevance, the current co-production literature has no clear-cut answer as the issue of citizens’ motivations to co-produce only recently came to the fore.

In our study, we focus on citizens’ engagement in co-production activities in the domain of safety, more specifically though neighbourhood watch schemes in the Netherlands and Belgium. Members of neighbourhood watch teams keep an eye on their neighbourhood. Often they gather information via citizen patrols on the streets, and report their findings to the police and municipal organization. Their signalling includes issues such as streetlamps not functioning, paving stones being broken, or antisocial behaviour. Furthermore, neighbourhood watch teams often draw attention to windows being open or back doors not being closed. Through the neighbourhood watch scheme, the local government and police thus collaborate to increase social control, stimulate prevention, and increase safety.

The opinions of citizens in co-producing these activities and their motivations for getting engaged in neighbourhood watch schemes are investigated using a ‘Q-methodology’ approach. This research method is especially suitable to study how people think about a certain topic. We asked a total of 64 respondents (30 in Belgium and 34 in the Netherlands) to rank a set of statements from totally disagreement to fully agreement.

Based on the rankings, we were able to identify different groups of co-producers. Each of the groups shares a specific viewpoint on their engagement, emphasizing for example more community-focused motivations or a professional attitude in the collaboration with both police and local government. To illustrate, in Belgium one of the groups identified are ‘protective rationalists’, who join the neighbourhood watch team to increase their own personal safety or the safety of their neighbourhood, but also weigh the rewards (in terms of safety) and costs (in terms of time and efforts). In Netherlands, to give another example, among the groups identified we found ‘normative partners’. These co-producers are convinced their investments help protect the common interest and that simply walking around the neighbourhood brings many results. Furthermore, they highly value partnerships with the police: they do not want to take over police’s tasks but argue they cannot function without the police also being involved.

The study shows that citizens being involved in the co-production of safety through neighbourhood watch schemes cannot be perceived as being similar to each other. Rather, different groups of co-producers can be identified, each of these reflecting a different combination of motivations and ideas. As such, the question addressed above concerning why people co-produce cannot be simply answered: the engagement of citizens to co-produce seems to be triggered by a combination of factors. Local governments that expect citizens to do part of the job previously done by professional organisations need to be aware of the incentives people have to co-produce public services. Their policies and communication strategies need to allow for diversity. For example, people who co-produce from a normative perspective might feel misunderstood when compulsory elements are integrated, while people who perceive their engagement as a professional task might be motivated by the provision of extensive feedback.

Carola van Eijk holds a position as a PhD-candidate at the Institute of Public Administration at Leiden University. In her research, she focusses on the interaction of both professionals and citizens in processes of co-production. In addition, her research interests include citizen participation at the local level, and crises (particularly blame games).

Carola van Eijk holds a position as a PhD-candidate at the Institute of Public Administration at Leiden University. In her research, she focusses on the interaction of both professionals and citizens in processes of co-production. In addition, her research interests include citizen participation at the local level, and crises (particularly blame games).

Trui Steen is Professor ‘Public Governance and Coproduction of Public Services’ at KU Leuven Public Governance Institute. She is interested in the governance of public tasks and the role of public service professionals therein. Her research includes diverse topics, such as professionalism, public service motivation, professional-citizen co-production of public services, central-local government relations, and public sector innovation

Bram Verschuere is Associate Professor at Ghent University. His research interests include public policy, public administration, coproduction, civil society and welfare policy.

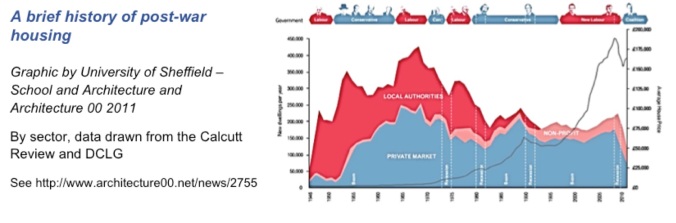

This evidence was summarised in a beautifully simple graphic (above) by the University of Sheffield School of Architecture. It evidences that the three decade long gap in our housing provision is simply because we’ve stopped building council houses. The answer to the fundamental question would seem to be to let councils (and housing associations) build again at some scale in order to supplement the relatively fixed-but-declining contribution of private developers.

This evidence was summarised in a beautifully simple graphic (above) by the University of Sheffield School of Architecture. It evidences that the three decade long gap in our housing provision is simply because we’ve stopped building council houses. The answer to the fundamental question would seem to be to let councils (and housing associations) build again at some scale in order to supplement the relatively fixed-but-declining contribution of private developers.