Paul Ward

Continuing our celebration of the dissertations of our Degree Apprentices. The use of data and data analytics is becoming increasingly important for all organisations – an essential asset to help effectively manage and transform local places. For a truly holistic data view of a city or place, multi-agency approaches to partnerships and data sharing are essential. What are the key governance considerations regarding a place-wide approach to data analytics?

This study found support for the concept of multi-agency partnerships and data sharing. Several barriers to data sharing were identified, including technical, organisational, political, economic and legal constraints.

The key governance factors to consider include the need to truly understand the problem which data is being asked to solve, to acknowledge and address the barriers as they are understood, to align overall governance with existing multi-agency governance structures and to create the relevant capacity for strategy and leadership regarding data and data analytics for the area.

Key findings:

- There needs to be senior level drive and ownership for data that will champion its use within an organisation and wider city, but in most cities there is not a ‘go to’ person or function that has lead responsibility and can provide guidance on data sharing across organisations.

- Local partnerships need to consider the purpose, vision and strategy for data use, the objectives that data sharing will achieve, how the public can engage and understand data, and how far organisational cultures support effective data use. Data sharing governance should be explicitly identified within existing multi-agency governance structures.

- Existing data sharing agreements are generally not designed to deal with the frequency, level and types of data that now need to be shared.

- Councils could lead the ‘democratisation’ of data as a public asset

- The study identifies two key elements of successful place-wide data sharing: a senior role identified as taking ownership and leadership responsibility for data, and a data strategy which defines the city’s ambition and vision for the use of data.

Background

Public authorities collect, hold and process a significant amount of data which could be used to make services more targeted and effective through design, delivery and transformation to improve outcomes whilst delivering efficiencies. The 2020 National Data Strategy seeks to make better use of data across businesses, government, civil society and individuals.

Data sharing has been in the spotlight as a result of the need for analysis to support interventions in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the increasing public awareness of data and data privacy, and work to encourage greater public uptake of digital services. For example, at the start of the lockdown period data was used to identify families in the case study city likely to become more vulnerable because of lockdown. The data had never been combined in this way before.

There is a growing need for a sustainable model and framework for data sharing across multiple agencies when considering the management and development of towns, cities and regions.

What we knew already

Organisations learn and develop when part of the organisation acquires knowledge that they recognise as important to the rest of the organisation, distribute and interpret this information efficiently and has effective organisational ‘memory’.

Data sharing can encourage innovation and help solve sector-wide challenges. However, trust in the use of public data is very low with many believing that they have no control over their personal data. A more trustworthy approach to public data is recommended by giving citizens more control over the use of their data.

Multi-agency approaches can deliver value and outcomes that would not be possible to deliver working individually. However, there are significant challenges such as a lack of willingness to collaborate, protecting individual interests, local rivalries, governance, funding, communication, and conflicting priorities.

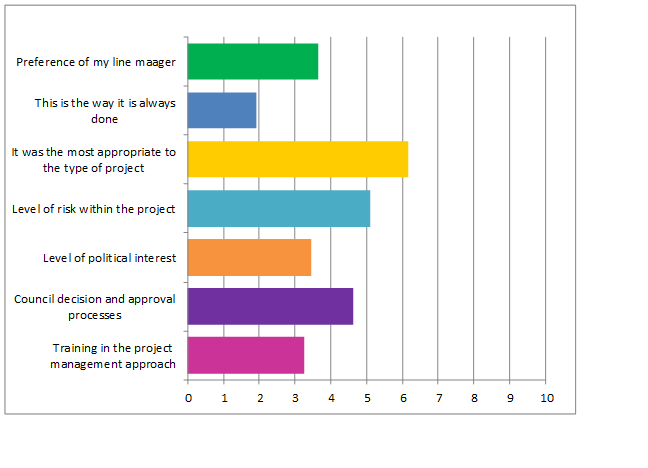

Multi- agency information sharing is difficult to achieve because of multiple barriers which may be technical (such as technically incompatible IT system, data standards or security requirements), organisational (such as risk aversion or lack of trust), political (such as avoidance of scrutiny, economic (lack of resources), and legal (concerns about the law around data sharing).

Frameworks for data sharing

Despite a number of these barriers being identified over twenty years ago they still resonant today. Existing data sharing agreements are, by design, very technical and detailed documents these do not address the use of data to understand policy problems. They are generally not designed to deal with the frequency, level and types of data that now need to be shared. In addition, in most cities there is not a ‘go to’ person or function that has lead responsibility and can provide guidance on data sharing across organisations.

Multi-agency working and governance

Every council area has important multi-agency partnerships in place, such as Health and Wellbeing Boards and Local Enterprise Partnerships. Most of these are established in a fairly traditional bureaucratic style with clear lines of authority, very detailed reporting arrangements and formalised decision making. The study found no desire for specific governance structures to be established purely for data sharing, instead this should be explicitly identified within existing multi-agency governance structures. The governance of these structures may need to evolve beyond the current bureaucratic model.

Local partnerships need to consider the purpose, vision and strategy for data use, the objectives that data sharing will achieve, how the public can engage and understand data, and how far organisational cultures support effective data use. There needs to be senior level drive and ownership for data that will champion its use within an organisation and wider city.

Councils could lead the ‘democratisation’ of data as a public asset – moving beyond allowing access to the data and making it easy for people to understand the data use under principles of transparency, integrity, accountability, and stakeholder participation.

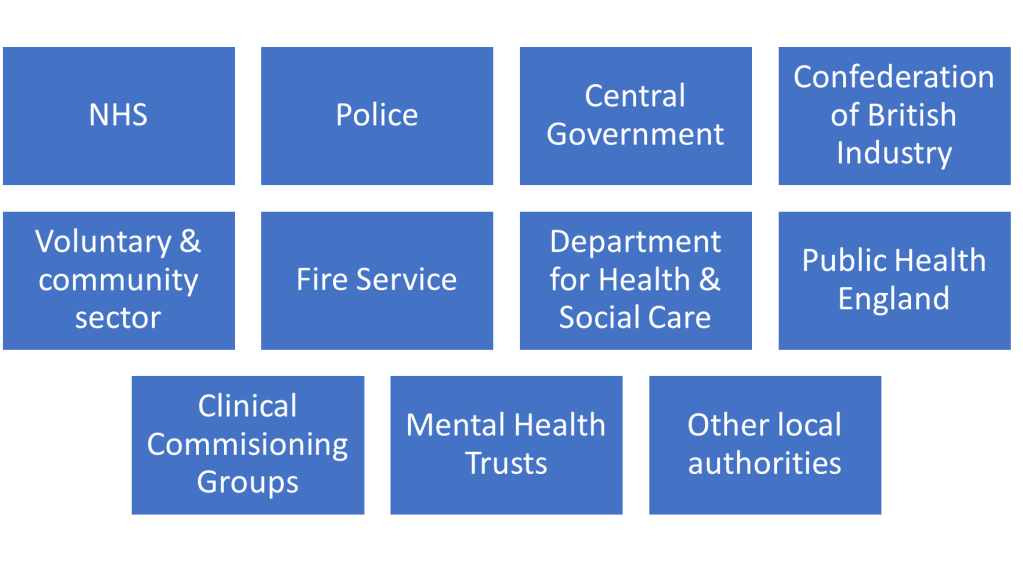

Examples of local data sharing partners

Conclusions

The study identifies two key elements of successful place-wide data sharing: a senior role identified as taking ownership and leadership responsibility for data, and a data strategy which defines the city’s ambition and vision for the use of data.

The findings suggest that the key governance factors to consider include the need to truly understand the problem which data is being asked to solve, to acknowledge and address the barriers as they are understood, to align overall governance with existing multi-agency governance structures and to create the relevant capacity for strategy and leadership regarding data and data analytics for the city.

_________________________________________________________________________________

About the project

This research was a Master’s dissertation as part of the MSc in Public Management and Leadership, completed by Paul Ward and supervised by Dr Louise Reardon. The project included detailed interviews with ten members and officers related to data sharing in an urban area.

Further information on Inlogov’s research, teaching and consultancy is available from the institute’s director, Jason Lowther, at [email protected]