Jason Lowther

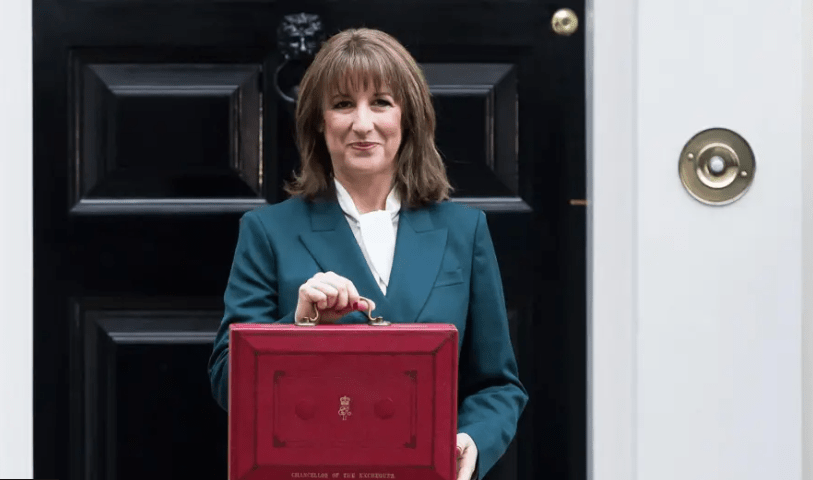

It’s hard to deny that the local government finance settlement this month marks big achievements for the ‘new’ (now almost two years old) government. Labour’s manifesto promised that “to provide greater stability, a Labour government will give councils multiyear funding settlements”, and the new finance settlement duly covers three years. By the end of this multi-year Settlement in 28-29, Core Spending Power will have increased by over 24% compared to 2024-25, equivalent to £16.6 billion. And this increased amount is distributed in line with a new formula designed better to match resources to needs (albeit with £440m last minute tinkering). There is much to celebrate here, which should give the government confidence to tackle another elephant in local government’s room: council tax.

Everyone knows that the council tax system is bad. It’s outdated (based on 1991 values, before an eighth of current housing was built), highly regressive (people in cheaper homes often pay a higher proportion of their property value than those in expensive homes), regionally unfair (a recent article in the i newspaper found 292 council areas across England paying higher rates of council tax than they would in the wealthy Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea), and over centralised.

As Inlogov recommended to last year’s Select Committee on The Funding and Sustainability of Local Government Finance, the Government should start to improve council tax by amending council tax bandings and giving discretion on the details of the scheme’s design locally, such as the rates in each band and discount/subsidy arrangements. The committee’s chair commented that “councils are trapped in a straitjacket by central government, with local authorities lacking the flexibility or control to devise creative, long-term, preventative solutions which could offer better value-for-money”.

There are already tentative moves to reform Council Tax in the different nations of the UK. The Scottish Government no longer caps council tax increases but leaves this decision to local elected representatives. This year’s Scottish Government budget also funded a revaluation of the highest value properties, with higher bands for properties valued over £1m (compared to the current highest band of £212,000), a change expected to affect around 1% of properties. This is less radical than most of the options considered in the IFS report the Scottish Government commissioned to inform its decision. In Wales, properties were revalued in 2003 and an additional council tax band above the highest band in England introduced. In Northern Ireland, domestic rates are based on 2005 prices and a percentage rate applied.

In the long term major transformation of local government funding is required, as the Select Committee concluded:

In the long term, only true transformation, supporting a clear vision of what the role of local government should be, can make the local government funding system fair and effective. Beyond mere stabilisation, the Government must consider approaches to strengthen the system, including allowing councils to set their own forms of local taxes such as tourist levies, and placing stronger responsibility on central government to fund the services it requires local authorities to deliver. Central government, so used to its tight control of local government’s purse strings, must learn to ease its grip and let councils have more power to control their own affairs, accountable not to Westminster, but to their own local electorates.

As the government enters its third year, agreeing long term plans for local taxes could make a big contribution to the “change” they promised and turbo charge the real devolution we need.

Dr Jason Lowther is director of the Institute of Local Government Studies (INLOGOV) at the University of Birmingham. He was previously Assistant Director (Strategy) at Birmingham City Council and has worked at the West Midlands Combined Authority, Audit Commission and Metropolitan Police.