Matty Edwards, Research For Action

Local authorities are under immense pressure to find savings whenever they can. After more than a decade of austerity, the collective deficit in the sector is expected to reach £9.3bn by next financial year. Local authority finances have also become increasingly speculative, as budgets are prepared on the basis of unpredictable grant allocations and single-year financial settlements, sometimes without audited accounts. Pressures to find new sources of income through commercial investments and private sector partnerships have also increased the complexity of council funding.

This creates a challenge: scrutiny of local government finance is more important than ever. Yet even with the best intentions, local authorities struggle to produce open and accessible financial information.

In a research collaboration between Research for Action and the University of Sussex, we set out to explore how financial information — such as council budgets and accounts — could be made more accessible to the public. Our research found that even experienced researchers, accountants and councillors struggle to find and understand local authority financial information.

We spoke to 26 people from the local government sector over three months this spring to examine barriers to making local authority financial information accessible to councillors and the wider public. Interviewees included councillors from a range of authorities, council officers, academics, accountants, journalists and key sector bodies like CIPFA.

Our key findings were a lack of standard reporting requirements, strained council capacity after years of austerity and a fragmented data landscape with no standard formats for publishing financial information. These barriers make it difficult to understand a single council’s finances and make comparisons across the sector, hindering effective scrutiny by councillors and journalists, and democratic participation by the public.

Some interviewees argued that accessibility was less of a priority in the face of a mounting crisis in local authority finances, but in our view, openness is not a luxury. It is key to effective local democracy.

How to improve open up council finances

Based on our findings, we set out a series of recommendations for greater transparency and openness.

The government should introduce new data standards for local government to improve accessibility, potentially via a Local Government Finance Act. This should include making financial information machine readable where possible and using accessible file formats. An easy win in this area would be to create a single repository for all local government financial information.

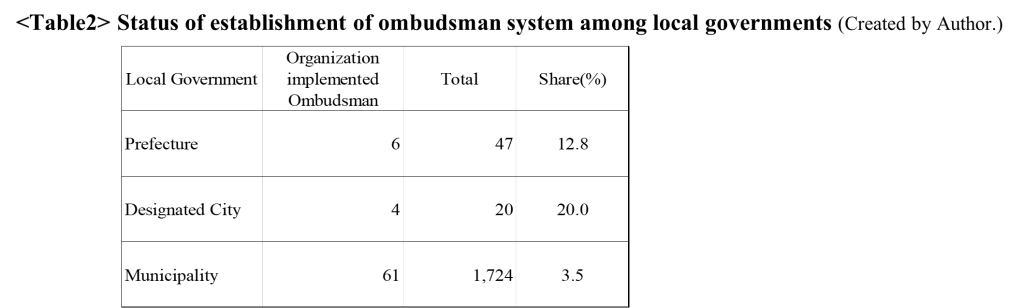

Local audit reforms are also an important piece of the puzzle. The new Local Audit Office (LAO) should be made responsible for local government financial data, including making it publicly available with tools to enable comparison and oversight. A more ambitious idea for the new LAO could be to create a traffic light warning system for the financial health of local authorities based on indicators that are timely and easy to understand, taking inspiration from Japan.

Council accounts were highlighted as a particularly technical and opaque part of local government finance. That’s why councils should be mandated to attach a narrative report to their annual accounts, as previously recommended by the Redmond Review.

We think that the Local Government Data Explorer, recently scrapped, should be replaced with a data visualisation that is genuinely accessible and interactive, perhaps taking inspiration from a dashboard created by academics in Ireland. There should also be funding for local open data platforms, because there have been isolated examples of successes, such as the Data Mill North.

The other part of the problem is that councillors often don’t have the knowledge and skills to properly scrutinise the complicated world of local government finance. That’s why we’re calling for greater support and training for councillors to enable better financial scrutiny, as well as public resources to improve literacy around local government.

While the sector faces great upheaval in the next few years through local government reorganisation and English Devolution, these reforms also present an opportunity to improve transparency – whether that’s at unitary or combined authority level.

We believe that greater openness will ultimately facilitate better public participation and healthier local democracies.

Matty Edwards is a freelance journalist based in Bristol who also works for Research For Action, a cooperative team of researchers that in recent years has investigated PFI, LOBO loans, the local audit crisis and scrutiny in local government.