Chris Game

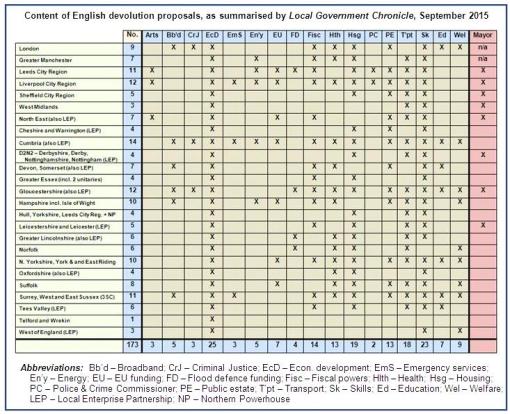

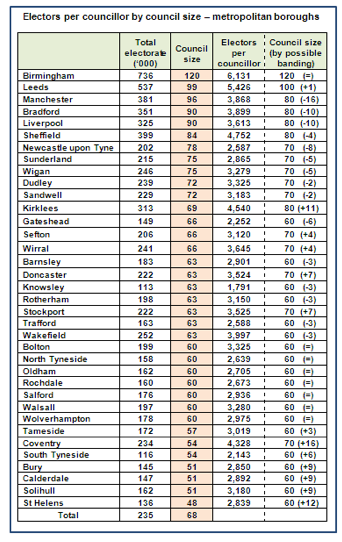

This blog’s main purpose is to place somewhere in the public domain some basic electoral data on council size. Basic, but not normally presented in a form that I’ve sometimes wanted for illustrative purposes. I’m hoping, therefore, there may be others who’ll find the data of at least passing interest, so here goes.

Hmmm. I can sense you’re containing your excitement, so I’d better explain why I’m bothering you with this stuff when you’ve already got the Greek debt, bombing Syria, Osborne’s budget, child poverty and Wimbledon to worry about. It’s the very top line, showing how Birmingham’s 120 councillors represent by far the largest electorates of any single-tier English authority – and arguably three times that 6,131 number in practice, as all metropolitan boroughs currently comprise entirely three-member wards.

And that’s it? No, but it’s interesting, surely, to have statistical confirmation of the demands we make on councillors by the exceptional scale of our so-called local government. In Birmingham this means having to get yourself known by, and every four years seek the votes of, up to 20,000 voters, who wonder (or ask you aggressively) why they see their ‘local’ councillor only at election times.

It’s interesting too, I think, to have again confirmation of how the Local Government Boundary Commission for England (LGBCE) – whose figures these are concerns itself exclusively with ward/division variance within, as opposed to across, authorities. Just one ward or division exceeding 30% variance from an authority’s electors-per-councillor average qualifies that authority for electoral review. Yet, for instance, the 93% variance between the overall average for Birmingham (incidentally, the 9th most deprived English district) and that for neighbouring Solihull (179th) is brushed aside as, in the words of the Polish expression, “not our circus, not our monkeys”.

But even that’s not it – or not entirely. The timing of the blog is prompted by the possibility/probability that the Commission is preparing to act in a way that would increase that Birmingham-Solihull variance from 93% to around 130%. More specifically, it is understood to have rejected a cross-party submission by Birmingham’s political leaders to retain the 120-member city council at its present size, on the grounds that it “runs counter to recommendations in the Kerslake Review which suggested 100 councillors as a maximum number”.

At which point, I should first mention that ‘council size’ will mainly be used henceforth in the relatively rare but Boundary Commission sense of “the number of councillors elected to serve a council”. Secondly, and more importantly, I should explain this blog’s secondary purpose: to update you on one stream of the action that’s followed last year’s Pickles-initiated review into the governance of Birmingham City Council, led by Sir Bob Kerslake in the months before his retirement as DCLG Permanent Secretary.

Collectively, the Kerslake review’s findings and conclusions were dire. Birmingham was judged a dysfunctional council, with a damaging corporate culture, a micro-managing leadership, poor member-officer relations, an arrogant attitude towards partnerships, with multiple plans and strategies not followed through, and no clearly articulated vision for the city.

The Review produced 10 main recommendations, several with multiple parts. The first and probably most important was the imposition of an independent Improvement Panel to “provide support and challenge” to the Council and oversee the implementation of an improvement plan.

The fourth recommendation, and inevitably one of the most contentious, was that the LGBCE should conduct an Electoral Review to enable the Council to move to what Kerslake felt would be a more effective model for representative governance – namely, replacing (by 2017/18) the current system of election by thirds from three-member wards to all-out elections every four years from single-member wards.

For what it’s worth, it’s a recommendation with which I completely agree. But here’s the thing – size and numbers, views and recommendations. Most of the Kerslake review’s many references to the size of Birmingham City Council seem – though it’s always clear – to be to the Council as an organisation, to its staff, or even to its residential population.

There’s no doubt that the reviewers also weren’t keen on the size of the council in the Boundary Commission sense (p.10). They felt it made the council (apparently in the organisational sense) difficult to run and had encouraged “individual councillors to micro-manage services”. But their major concerns were the size of the three-member wards – which meant “some councillors are struggling to connect their communities with the council – and the pattern of election by thirds, which “has not helped the council’s ability to take strategic decisions.” These were the changes called for in the Electoral Review recommendation, which contained no mention of councillor numbers per se.

Council size was treated differently in the Kerslake review from election by thirds. It easily could have been a whole or part-recommendation, but it remained merely a “view” of the report’s authors that “there needs to be a significant reduction in the current number of councillors” (p.26). I don’t feel this is academic nit-picking. Words have meanings, and, were council members to argue that a view shouldn’t carry the same weight with the Commission as a recommendation, they would seem to have a point.

The 100-councillor figure, moreover, wasn’t even a view, or, for that matter, a maximum; more a conveniently round-numbered illustration (p.26): “For example, by creating 100 mainly single-member wards, the average population of a ward could be reduced to just 10,730 from 13,413. This would result in a direct saving of around £1.6 million over five years.” Note that casual “just 10,730”, which would be nearly half as many again as the highest average ward population of any other single-tier authority, EVEN IF that authority too (Leeds) were forced to switch to single-member wards.

As already emphasized, however, the LGBCE, regards such comparisons as irrelevancies. So, if Birmingham is going to be deemed not to merit a council of more than 100 members, what case will the Commission make to justify driving it even further out of line with other major metropolitan councils?

The Commission’s own 50-page Technical Guidance suggests it sees itself as independent of government, consultative where necessary, and open-minded, with no predetermined views of council size or councillor numbers. It believes each local authority should be considered individually, and dislikes comparisons of council populations and electorates, any mathematical criteria or formulae, and also arguments based either on population projections or future cost-savings. It is evidence-driven, provided the evidence is substantiated and relates specifically to the characteristics and needs of the review authority and its residents – the governance arrangements of the council, its scrutiny functions, and the representational role of its councillors in the local community.

All of which sounds fine. If 120 councillors with already statistically the heaviest workloads in the country with by far the highest population:councillor ratios in Europe can’t effectively justify their own continued existence, then perhaps they don’t deserve one. But then, if the Commission really did start with no predetermined views, why the rumours of it following the apparently cost-driven notions of the ministerially appointed Kerslake review not merely to the letter, but beyond? Odd.

As in so much of our local government practice, other countries have other ways of doing these things. Most democratic countries pay at least lip service to every vote being of equal weight, and therefore start off with a table rather like mine, listing numbers of either registered electors or all residents in each municipality, precisely so that comparisons CAN be made across councils of the same type.

Sweden is, well, Swedish, and details the whole council size procedure in Chapter 5 of its Local Government Act – and then translates the whole thing into English!. For a start – and a very good one, for any voting assembly – all total councillor numbers must be odd.

Second, an electorate-based formula sets MINIMUM numbers, which municipalities themselves may, and regularly do, increase: up to 12,000 electors – 31 councillors; 12,001 to 24,000 – 41; 24,001 to 36,000 – 51, and so on. Stockholm’s 660,000 electors, should any mathematicians be wondering, get just the 101 councillors, not 561.

Of course, not all countries are as Scandinavian in their determination of council sizes – though Purdam et al’s 2008 CCPR Working Paper is still one of the few academic examinations of these matters. But few, unaware of our now constitutional requirement that Manchester be advantageously treated in all things, would see the disparity between that city’s 96 councillors representing an average of 3,868 electors, Leeds’ 99 representing 5,426, and Birmingham’s current 120 representing 6,131 as some bizarre kind of democratic virtue. As for Kerslake’s suggested 10,730, they’d surely dismiss it as some sub-category of ‘ze Ingleesh sense of humeur’.

The table’s final column shows potential council sizes under a rough-and-ready Swedish-type formula, adjusted for the greater size of our metropolitan authorities: up to 200,000 electors – 60 councillors; 200,001 to 300,000 – 70; 300,001 to 400,000 – 80, and so on. Different bandings would obviously produce different results, but this one has Coventry, St Helens and Kirklees as the biggest gainers, Manchester, Bradford and Liverpool as the biggest losers, and Birmingham – well, there’s a coincidence – retaining its current 120 members.

In principle, one possible partial explanation of Manchester’s more generous councillor allocation could be that on current figures it’s the 4th most multiply deprived of England’s 326 district authorities – were it not that, as was noted above, and also in the Kerslake Supporting Analysis noted (p.13), Birmingham is only just behind it at 9th.

Kerslake doesn’t link deprivation to any consideration of council size, but the Scottish Boundary Commission does. In fact, it uses BOTH population size and level of deprivation as two of its three principal criteria for determining council numbers.

North of the border, therefore, Birmingham’s current population size, its dramatic projected growth – an additional 150,000 by 2031 – and its multiple deprivation would all militate against any cut in its councillor numbers. If the English Commission sees things markedly differently, it will be interesting to hear why.