Richard Berry

The e-petitions system introduced by the UK Parliament has gained considerable attention in recent years. This is often when a noisy cause claims hundreds of thousands of signatures and forces its way onto the parliamentary agenda. At the time of writing, for instance, there are live petitions for suspending all immigration, rejoining the European Union, reducing the state pension age and changing the parliamentary electoral system.

One might question the feasibility of these suggestions. They may indicate high levels of popular support for an idea, however they call for major shifts in government policy, significant investment of public funds or far-reaching legislative change. Governments would ordinarily have determined their stance on such ideas without any further prompting from petitioners, even significant numbers of them.

In contrast, local government should be fertile ground for petitioners. The subjects of petitions submitted to councils are often hyper-local issues and, in theory at least, much more realistic in their ambitions.

Catherine Bochel and Hugh Bochel have studied the use of petitions in English local government and described the benefits to both local authorities and their residents. In summary, they have found petitions can provide access to politics for citizens without requiring a significant amount of resource. A well-run petitions system can come to decisions that are seen as fair by the petitioners, even if they do not get their desired outcomes, and can provide an educative function. For councils, a petitions system can be a means of receiving ideas and information, which may inform future policy development and service provision.

The London Assembly Research Unit has recently conducted research into how petitions are used in local government in London. We found that 28 of the 32 London boroughs (87.5%) offer an e-petitions platform on their websites. In a couple of boroughs these are only accessible to registered users of the site – that is, local residents with an online account with the council – but in most cases they were accessible to any visitor to the site.

Looking at the calendar year 2023, we were able to obtain data on the number of submitted petitions for 26 boroughs. There was significant variation, with Barnet Council receiving 45 petitions and some not receiving any. The average per borough across the year was 11 petitions.

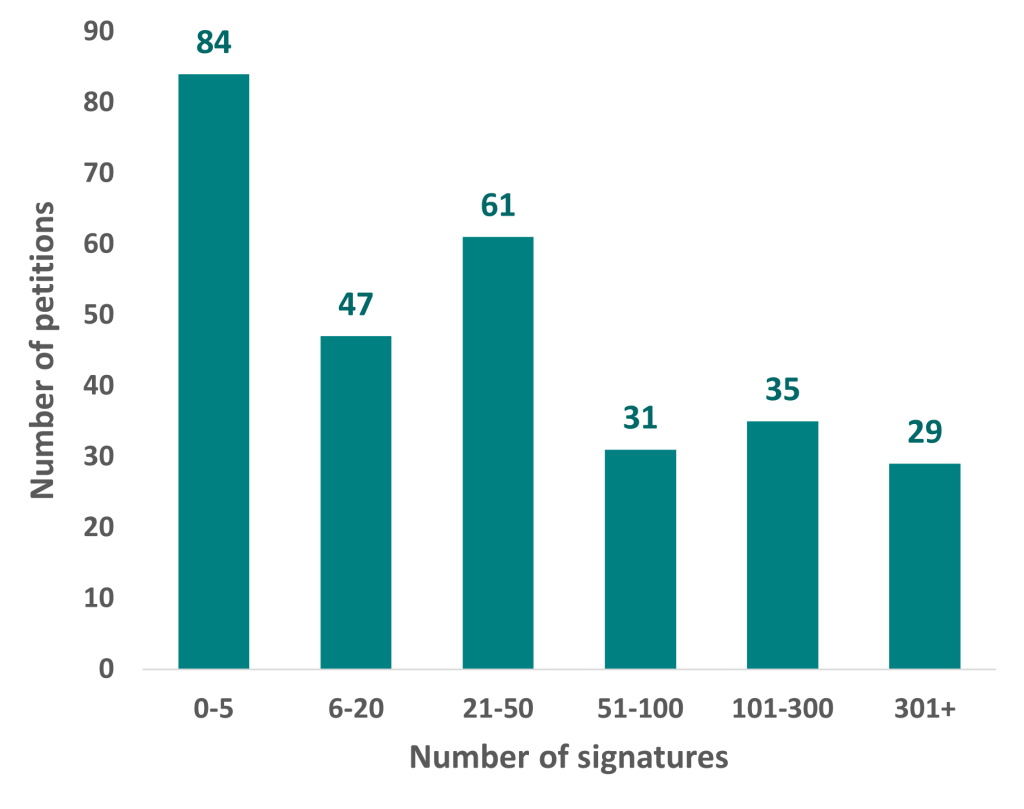

Chart 1 below presents information on the number of signatures received per petition. Most received relatively few signatures, with 26 being the median number of signatures. However, a few received very high numbers – 11 petitions across all boroughs received more than 1,000 signatures – bring the mean number of signatures per petition up to 187.

Chart 1: Number of signatures on e-petitions to London boroughs, 2023

Source: London Assembly Research Unit. Based on petitions data for 26 out of 32 boroughs

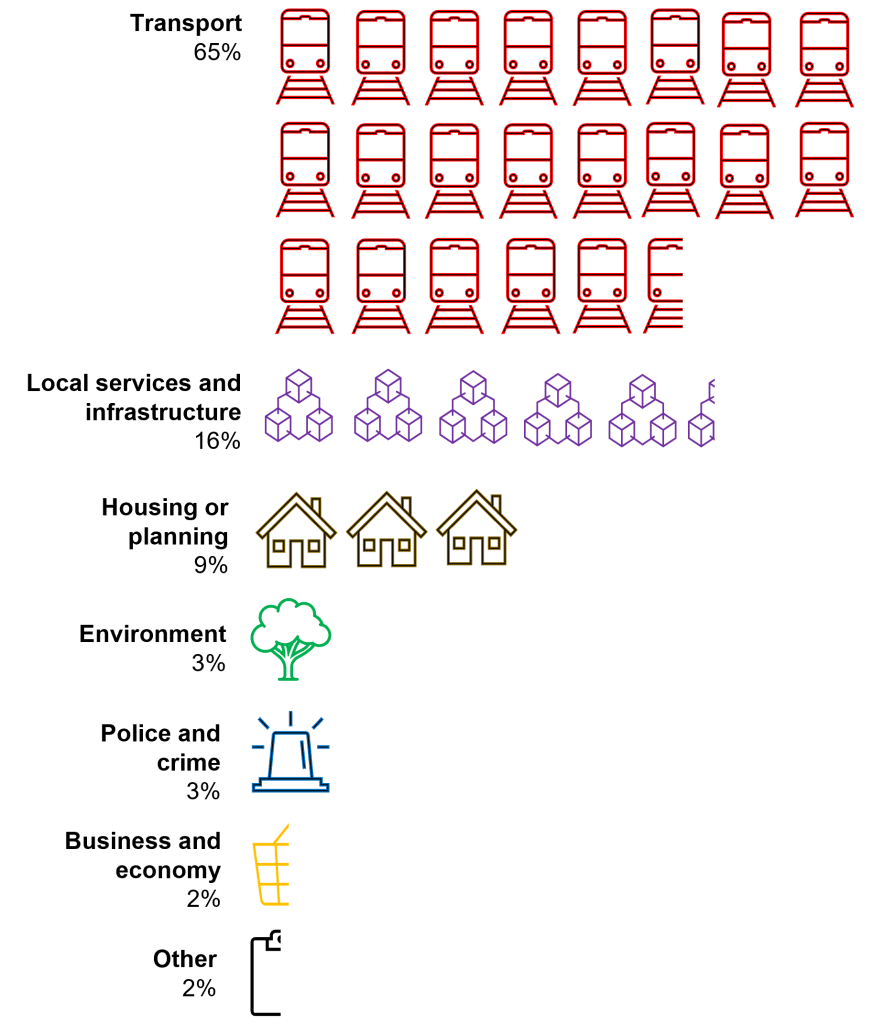

We also considered the topics of petitions submitted to boroughs. We found, somewhat surprisingly, that there was one dominant theme, transport, as shown in Chart 2.

In London, responsibility for most public transport and control of major roads is held by a city-wide strategic authority, Transport for London, overseen by the Mayor of London. Yet boroughs still control the majority of London’s roads, and we found this is where many petitions focused, as people sought changes to the streets where they live.

We see, for instance, that 71 residents of the London Borough of Ealing have called for the enforcement of the speed limit on one local road. 157 residents of the City of Westminster supported moving the location of an e-bike parking bay that had been blocking the pavement in one area. In the London Borough of Sutton, 52 residents signed a petition for the resurfacing one road in a state of disrepair.

Chart 2: Topic areas of e-petitions submitted to London boroughs, 2023

Source: London Assembly Research Unit. Based on petitions data for 26 out of 32 boroughs

The growth of online petitions systems has been the perhaps the most important development of recent times in this field. Another change that has coincided with the rise of e-petitions is that, from being the passive recipient of petitions generated externally, local authorities are now playing an active role in hosting the online platforms on which petitions are managed.

This was encouraged by the 2009 Local Democracy, Economic Development and Construction Act, which places a requirement on English local authorities to operate schemes for the handling of petitions from local residents. Although this requirement was repealed just two years later in the Localism Act 2011, systems had been introduced and in many cases have remained. In a very real sense, they are helping to facilitate campaigns focused on challenging councils’ own policies, which itself is a sign of a healthy democracy.

Richard Berry is the manager of the Research Unit at the London Assembly, which provides an impartial research and analysis service designed to inform Assembly scrutiny. The author would like to thank Kate First and William Weihermüller for conducting research cited in this article. All publications from the London Assembly Research Unit are available here.