Chris Game

In her recent blog on financially distressed councils in general and West Somerset DC in particular, Catherine Staite suggested that we should be talking more about “streamlining the machinery of local government … merging smaller councils”, and in effect institutionalising some of the multiplying numbers of apparently cost-saving shared service and shared staffing arrangements

Hardly had Catherine’s blog hit the page, however, than things had moved on – certainly for hapless West Somerset. Despite its being a key recommended solution of both the LGA and the former Local Government Minister, Bob Neill, it seems West Somerset may not after all be one of the smaller councils destined for oblivion by merger. Instead, Neill’s successor, Brandon Lewis, has come up with a cunning plan to – as it’s put in the report going to the full council this Wednesday – “retain the ‘sovereignty’ of the Council as the local democratic accountable body in West Somerset” (p.34).

It’s good that ‘sovereignty’ word is encased securely in the kind of quotation marks used for unfamiliar or ironic usage – because it’s not one generally considered applicable to any UK local authority, and there certainly doesn’t seem a whole lot of it in the plan for West Somerset. Rather, it takes on almost the exact opposite of its usual meaning: namely, following to the letter the Minister’s lengthy list of demands and conditions, in exchange for which it has the unique ‘opportunity’ (my quotes, this time) to create a new model of operation by becoming a ‘Commissioning Authority’.

No, sorry, a solely Commissioning Authority, for in this case the Council would commission other service providers, mainly neighbouring councils, to provide all the services it decides West Somerset residents require, retaining only a skeleton staff to manage the arrangements and monitor performance. Yes – the minimalist council, once merely a gleam in the mind’s eye of Thatcherite Environment Secretary, Nicholas Ridley, has finally arrived. Remember the punchline to his vision of a council meeting just once a year, to hand out contracts for its various services: “I wouldn’t mind paying those councillors attendance allowances”. How we laughed. I wonder if West Somerset members will see the joke, as they learn the details of – to use a term that seems not to feature in Wednesday’s council report – their ‘virtual authority’: not physically existing as such, but made to appear to do so by software, or in this instance Ministerial soft-soap.

I want to return, though, to Catherine’s blog and her exhortation to talk about these things, and mergers in particular, before they reach the stage of Ministerial intervention. Here at the uni we’re all for more talk and critical inquiry – can’t get enough of them. So, in the interests of helping things along, I thought I’d perform an Arsène Wenger role and add a bit of perspective to the discussions.

The French-born Wenger, for those unfamiliar with Planet Football, is the longest serving and most successful manager of the English Premier League side, Arsenal. Despite his outstanding record, he is currently getting flak from both the media and club supporters after, by Arsenal’s recent standards, a poor start to the season. Wenger’s understandable response is to call for less emotion and more perspective, claiming that the club is in fact “in fantastic shape”.

No, I’m not about to claim that West Somerset, or indeed any other authority in these stressful times, is in fantastic shape. I do wonder, though, what it says about our system of LOCAL government that it apparently cannot accommodate a principal council of the size and with the potential resources of West Somerset, and when its own representative Association declares it “not viable as a unit of local democracy and governance over the longer term”. Why are we – a modest 80th among the territorially largest countries in the world – so desperately keen to have its largest-scale and least-local local government?

First, a few stats. The currently 28-member West Somerset DC was created in 1974 from a merger of two urban and two rural district councils (95 councillors in all), at least one of which – Minehead, a largely self-contained historic coastal town of just over 10,000 – would undoubtedly still be a principal council in its own right in many European countries. West Somerset’s population is 35,000, with the oldest average age in the UK and spread across an area of 740 km² (290 mls²), including much of Exmoor, and the Quantock and Brendon hills. The result is a population density or sparsity of 48 people per km², compared to the UK average of nearly 400. Unfortunately, such extremes count for little when arguing grant settlement figures with London-based civil servants inclined to dismiss all such ‘special case’ bids as ‘that’s what they all say’.

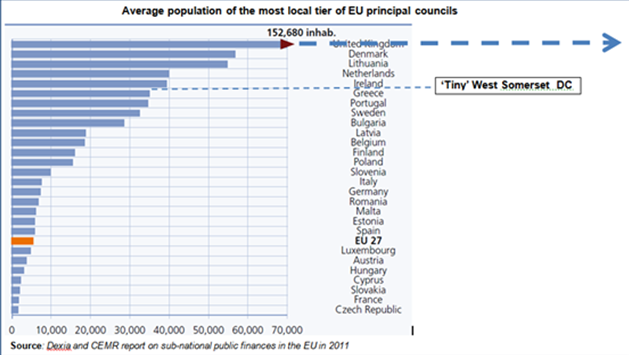

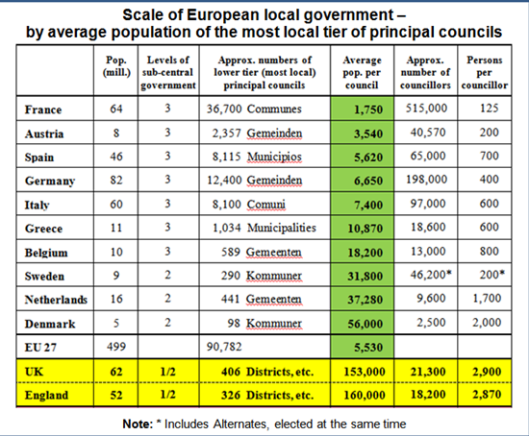

Media reports of West Somerset invariably attribute its alleged unviability to its – meaning presumably its 35,000 population – being so ‘small’ or even ‘tiny’. Which it is – but only by the UK’s extraordinary, Brobdingnagian standards. Among EU countries, as shown in the table below, it is more than six times the average size of the lower-tier authorities in what are mostly two- or three-tier systems (Wilson and Game 2011, p.275). If, notwithstanding this being a Wengerian perspective, we take out the distorting influence of the Lilliputian-scale French communes, it’s still well over four times the average size. Try putting the figures on a graph, and the UK not only goes off the end of the horizontal axis; it would require a whole second page for itself

(Source: Wilson and Game 2011: 275).

(Source: Wilson and Game 2011: 275).

(Source: Dexia-CEMR, page 6)

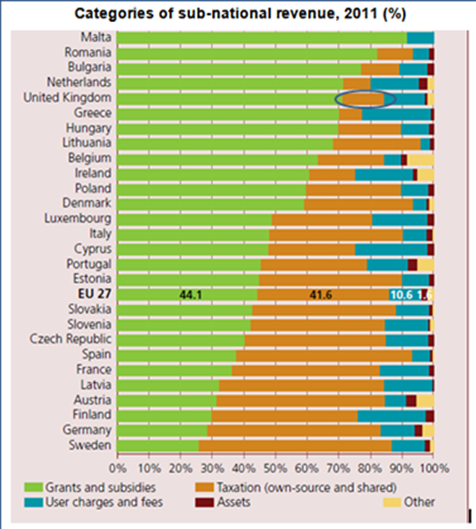

Most of these other EU countries’ municipalities, though generally much smaller than English districts, also have a constitutional power of general competence, and, even more relevantly in the present context, access to a number of different local taxes and tax bases – as can be seen in another graph from the same Dexia/CEMR publication (p.15). On average among the EU 27, the proportions of local revenue coming from central government grants/subsidies and from local/shared taxation are roughly equal; the UK ratio is 6 to 1. Across the EU, local taxes account for between 35 and 40% of local government revenue and between a fifth and a quarter of total tax revenues. Corresponding UK figures in 2011 were 12.7% and 6.2% (Source: CCRE).

(Source: Dexia-CEMR, page 15)

(Source: Dexia-CEMR, page 15)

West Somerset is simply an extreme example of UK local government’s general financial weakness and central dependency. It currently has, if I read the figures correctly, the lowest council tax base of any English district, minimal reserves on which to draw, and is facing a reduction in its revenue support grant both more savage and more immediate even than that for which it was already budgeting. Its alleged unviability is not, as the LGA described it, as a unit of local democracy and governance, but purely financial. It is the victim of a rigidly centralist funding system being screwed down so tightly that the representative body of a sizable local area and population can no longer do the job for which it was elected.

One final point. Catherine Staite referred in her blog to Denmark’s recent municipality merger programme as one that might have lessons for this country: “councils joined together voluntarily with their neighbours until they achieved the best possible combination of size and geography to deliver economies of scale and locally accessible services”. As it happens, other Nordic countries and/or their citizens have resisted the Danish/British ‘bigger must always be better’ thesis – Norway and Sweden almost completely, Finland and Iceland considerably – but that is not my concern here.

The Danish structural reforms, if not the mergers themselves, were strongly centrally driven, incentivised, and extensive. The number of municipalities was cut by nearly two-thirds, from 271 to 98, the number of councillors by 45%, and the average population size increased from under 20,000 to 56,000 (see table above). However, there still remain 7 municipalities with populations of under 15,000 – the ‘special cases’ that our system seems unable, or unwilling, to accommodate.

It was actually suggested a couple of years ago that this should be the Government’s approach to West Somerset’s exceptional and increasingly dire situation: focus on the nature and needs of relatively small councils, rather than insisting on their adoption of a model designed for much larger councils. They could be allowed ‘flexibilities’, like lighter regulation, and not having to produce separate corporate, improvement and service plans. Above all, though, the Government might consider increasing, rather than cutting, their grant funding and allowing a council tax increase in excess of the then 3% cap.

And which hare-brained, ivory tower academic came up with that notion? None, actually – it was Bill Roots, ex-Westminster Chief Executive, and author of one of the first independent reports on West Somerset. A pity no one listened.

Chris is a Visiting Lecturer at INLOGOV interested in the politics of local government; local elections, electoral reform and other electoral behaviour; party politics; political leadership and management; member-officer relations; central-local relations; use of consumer and opinion research in local government; the modernisation agenda and the implementation of executive local government.