Chris Game

Some social phenomena are exceptionally tricky to measure: the black economy, white-collar crime, illegal immigration. So when someone claims to have done so, no matter how flaky their findings, they attract huge, and largely uncritical, media attention. Like last week’s excitement about the scale of NHS fraud.

The catalyst was a Panorama programme – The Great NHS Robbery – that needed some pre-transmission headlines. The programme consisted mainly of specific cases of GPs, dentists, pharmacists, private contractors and suppliers who’d been found guilty of defrauding the NHS. It alleged that the Government’s official NHS fraud figure of £229 million p.a. is a huge under-count or under-estimate, and suggested that, having cut the staffing and budgets of NHS Protect and other fraud investigators, the Government was turning a proverbial blind eye to the scale of the problem, especially by comparison with the increased resources it allocated to the detection of the much smaller quantum of benefit fraud.

Old cases and political sniping, however, don’t make major headlines. What Panorama needed were some seriously big and scary figures, and fortunately there were some to hand – just down the M3 at the University of Portsmouth’s Centre for Counter Fraud Studies (CCFS). By happy coincidence, the CCFS was about to co-publish, on the very same day as the first showing of The Great NHS Robbery, a report analysing, as the programme put it, “the most rigorous data on health care fraud in the world”, and containing some “staggering” findings for the NHS.

The BBC had its headlines – “NHS fraud and error costing the UK £7 billion a year” – and Panorama had its audience. Other contemporaneous media headlines were all apparently taken either from the BBC’s plug story or the programme itself. Some were fractionally more cautious, like The Guardian’s “NHS fraud could be as high as £5 billion a year, says former health service official”; others less, like the Nursing Times’ “Fraud costs NHS £7 billion – enough to pay for 250,000 nurses”.

None of the authors, it seemed, went to the CCFS report to check how the loss figures were arrived at and what they represented – possibly imagining that a global report on such a complex and technical topic, representing the product of several years’ research, would be vast, probably undownloadable, and incomprehensible to the average reader.

Interestingly, though, it’s none of these things. The Financial Cost of Healthcare Fraud 2014: What data from around the world shows runs to just 16 pages, including the two covers. The rest comprises: Contents, Foreword, three prefaces, three pages about the authors and publishers, a full-page picture, a blank page … and a 4½-page ‘report’. There are no “data from around the world”, so, even with the glossy pictures, you could, if you wished, download it in about a second.

However, to save you having to plough through all 4½ pages yourselves, let me take you through the methodology step by step.

1. Do a literature review of the 92 studies of healthcare fraud and error losses that you’re able to find that have been undertaken since 1997 – not ‘globally’, but in languages you can understand: the UK, US, France, Belgium, the Netherlands and New Zealand;

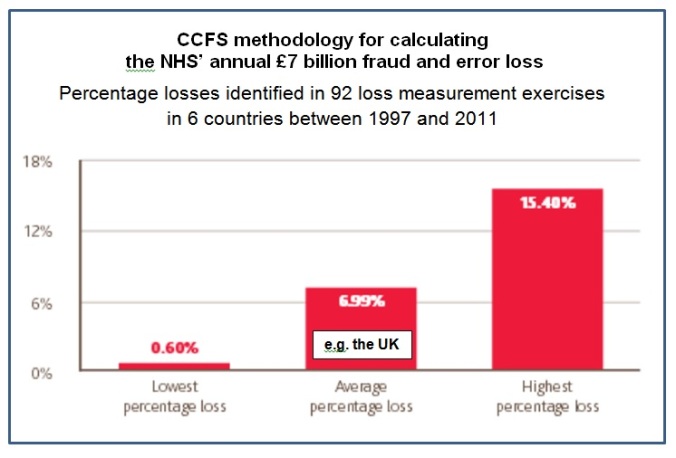

2. Don’t worry about the studies being in numerous completely different areas of health care, but average out the quoted financial loss figures in all 92 studies and cite that average with real authoritative precision – i.e. not 7%, but 6.99% – because, remember, these have to look like “the most rigorous data on health care fraud in the world”;

3. Globalise your ‘research’ by finding a figure for global healthcare expenditure for some recent year (no, not ‘global’ as in your six countries, but really global) – say, $6.97 trillion for 2011 (or £4.48 trillion) – and again don’t worry about whether they’re US or International $$ or what the figure actually represents, for this is one of those footnote- and reference-free reports;

4. Divide (3) by (2), and again state the sum with great precision: that this shows that £313 billion is being lost by the world’s healthcare services each year – or 25% more than when you last did the sum in 2008;

5. Guess – because you’ve apparently no evidence one way or the other – that the financial integrity of the NHS is probably about average for the six countries you’ve studied, and assert that it is therefore losing 7% of expenditure each year – or £7 billion out of its roughly £100 billion total – in ‘fraud and error’, making sure, of course, that you emphasise the fraud bit.

6. Add a little diagram, as shown below with the addition of my clarification of where the UK figure comes from.

I must confess at this point to having misled you a little. I mentioned that the report contains no “data from around the world”, and indeed there are no figures for the UK or any other individual country. The £7 billion came in the Panorama programme, from one of the report’s two principal authors, Jim Gee. Gee is the former health service official referred to The Guardian’s headline: former CEO of the NHS Counter Fraud Service and now Director of Counter Fraud Services at BDO LLP – not, sadly, the British Darts Organisation, but Binder, Dijker, Otte and Co., an accountancy firm specialising in anti-fraud services – and Chair of the CCFS at the University of Portsmouth. Gee left it to the programme’s presenter to add that “he puts more than £5 billion of that £7 billion down to fraud, rather than financial error” – which explains the other part of The Guardian’s headline.

Though certainly not on the same scale as its undercover filming of LSE students in North Korea, Panorama’s decision to rest the central argument of this programme on such flaky statistics, produced at least in part to further the interests of a self-promoting business services company, seems to me another clear editorial misjudgement. Certainly it irritated me when I pieced together the above account and realised that in effect I’d been conned.

Much more importantly, though, it must in anything other than the short term undermine, rather than substantiate, the key points the programme was seeking to make: that the way the Department of Health currently measures and estimates NHS fraud is grossly inadequate and damagingly misleading; that governments, and this Government in particular, see it in their interests to under-record the scale of fraud (and financial error, for that matter); and that more, rather than less, funding should be being invested in fraud detection and inspection services.

The sad truth is that Panorama seized on CCFS/BDO’s £5 to £7 billion because there was nothing better or more accurate available. Jim Gee’s ‘methodology’ suggests to me that he’s probably underestimating global healthcare financial losses and overestimating those of the NHS, but neither I nor the Government have any way of officially demonstrating it. Nor is there any likelihood of the Government, since it is substantially in denial, embarking on a programme to reduce the losses by up to the 40% within 12 months that Gee, wearing his BDO hat, considers feasible. I doubt if many others agree, but, to adapt the proverb: in the land of the dataless, the one-figure man is king.

Chris Game is a Visiting Lecturer at INLOGOV interested in the politics of local government; local elections, electoral reform and other electoral behaviour; party politics; political leadership and management; member-officer relations; central-local relations; use of consumer and opinion research in local government; the modernisation agenda and the implementation of executive local government.