Chris Game

Remember the old London bus joke: you wait for ages, then three come along at once? Well, some local government finance anoraks have been waiting ages for a 114, and now two 24s arrive, almost in mini-convoy.

Not buses, of course – but key sections of Acts of Parliament. Section 114 of the Local Government Finance Act 1988 requires a council’s Chief Finance Officer (CFO) to issue a s114 Notice reporting to all elected members an actual or impending seriously unbalanced budget.

As indicated, they’re infrequent, issued only in what CIPFA terms (p.3) “the gravest of circumstances” – current spending way beyond budget, reserves virtually exhausted, no imminent solution. Their impact too is grave – effectively freezing spending until councillors agree measures to achieve a balanced budget. But … they do keep the crisis in-house.

The alternative – being required to wash your dirty linen in public – is the dreaded Section 24 of the Local Audit and Accountability Act 2014. Here, a council’s external auditors append a written s24 ‘Recommendation’ to their Annual Audit letter, “copied to the Secretary of State”. The recommending and copying may sound chummy, but it’s the bullet-shaped chumminess of a Mafia ‘message job’. S24 Notices are very nasty, and happily very rare – or were.

Recently the Isles of Scilly Council received one, which is interesting in itself, since not everyone’s clear what it actually is: not part of the already enormous Cornwall Council, but a sui generis unitary authority – in a class of its own.

It’s considerably smaller than my own authority, Birmingham City Council (bear with me, it’s not that daft a comparison), with one-480th of its population – though, interestingly, one councillor for every 109 residents, compared to Birmingham’s post-2018 ration of one for every 10,900. And, as a genuine unitary, it has Birmingham’s major functions, including an airport, plus fire services, water supply, sea fisheries and coastal defence.

Unfortunately, Scilly’s unique status doesn’t exempt it from the austerity pressures and grant cuts faced by all English councils. It’s suffering badly, and its external auditors concluded that – with £3 million needed to pay staff and suppliers, no council tax income for the last two months of the financial year, and reserves down to £0.5 million – the law required Section 24, ‘recommending’ in terms (p.37) that the Council get its whole financial act together, extremely pronto.

Its impact, warning notwithstanding, can be surmised from the reaction of the eminent former Labour leader of the previous council to have received a s24 missive, just last November from coincidentally the same auditors, Grant Thornton. “The most concerning audit letter I have seen in all my [36] years on the council” was Cllr Sir Albert Bore’s verdict – the council being Birmingham, and the equivalent budget black hole not £3 million but pushing £38 million.

Just as Aristotle’s single swallow did not a summer make, two s24s don’t themselves make a systemic winter crisis. They’re surely, though, a sign – given that not one such report was issued to any council during the whole four-year 2010 spending review period, and we’ve now had two in two months.

But a sign of what? That’s rhetorical. I’m categorically not a local finance expert, and in this blog’s limited remaining space there are no answers – just three observations.

- Why no s114s?

In the past we’d see them at least occasionally. Now there are rumoured sightings – e.g. in Northamptonshire – yet what have materialised are the two s24s, the proverbial nuclear option. It’s been suggested that the (post-1988 Local Finance Act) statutory duties of Social Services Directors mean a s114-prompted total spending freeze could prevent, say, a vulnerable child being placed in care. But CIPFA Chief Executive Rob Whiteman has rejected this interpretation.

- Please, not the B-word

There’s unfortunately no way of avoiding the media headline, but Scilly, Birmingham and probably any financially struggling English councils aren’t about to ‘go bankrupt’ in the sense in which the word is commonly understood. UK councils, unlike US local government or our own national government, are statutorily required to set each year a balanced budget. Running a deficit of the smallest fraction of Detroit’s nearly $400 million in 2013 is simply not possible – indeed, a very s(c)illy idea.

3. But watch for those ‘statutory duties’

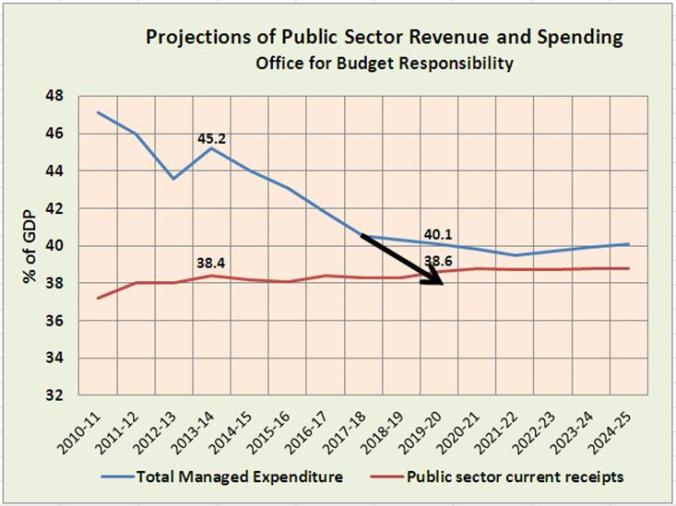

So not bankruptcy in the normal legal sense, but almost daily signs and public warnings – Conservative Surrey’s seriously contemplated 15% council tax referendum, tax hikes all round of approaching 5%, hitherto protected adult care budgets now being cut and 13% of responding councils in the MJ/LGIU 2017 State of Local Government Finance Survey –reporting “a danger they would no longer have enough funding to fulfil their statutory duties in the coming year”.

Which would mean facing legal challenge for failing to meet those statutory duties and/or declaring ‘technical insolvency’. Not ‘bankruptcy’, note; but, as the famous duck test puts it: if it looks like, walks like, and quacks like a duck ….

Chris Game is a Visiting Lecturer at INLOGOV interested in the politics of local government; local elections, electoral reform and other electoral behaviour; party politics; political leadership and management; member-officer relations; central-local relations; use of consumer and opinion research in local government; the modernisation agenda and the implementation of executive local government.