Chris Game

My recent blog, endeavouring to mark our first six Combined Authority mayors’ 100 days in office by comparing their CAs’ corporate logos, was accompanied by a regret about not offering something more substantive. Prompted partly by the recent encouragement to prospective contributors to “accompany your blog, if possible, with a photo or image”, this is an attempt to do so.

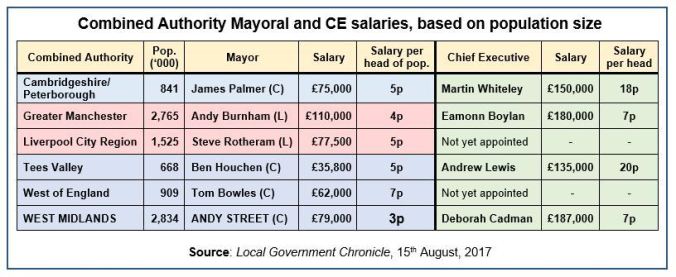

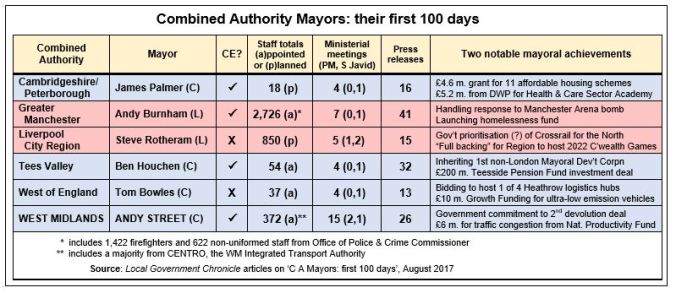

The other, completely indispensable, prompt was the Local Government Chronicle team’s recent extensive assessment of the mayors’ first 100 days. For other purposes, I tabulated some of the LGC data, which enables more to be fitted into one blog than might otherwise be possible, and also explains the tables’ West Midlands upper case emphasis.

The first table is compiled from Mark Smulian’s pay analysis, showing that, dividing the mayors’ annual salaries by the size of the population they serve, the “cheapest” mayor is West Midlands’ Andy Street – his £79,000 p.a. representing just under 3p per head. The calculation formula is obviously crucial. Street’s is far from the lowest salary, but it’s nearly a third lower than Andy Burnham’s in the slightly less populous Greater Manchester. And it remains lower (2.8p against 3.4p), even allowing for Burnham’s first public mayoral act being to launch a homelessness fund, pledge 15% of his own salary towards it, and encourage others to do likewise.

More conventional comparisons – based, say, on the CAs’ budgets – are difficult, since, beyond their Investment Fund and transport grants, we’ve little idea of what they’ll eventually be. So, for what it’s worth, by the same measure Sadiq Khan costs Londoners 1.7p p.a., and Birmingham City Council leader, John Clancy, costs me 6p. Which is only fractionally less than will WMCA chief executive, Birmingham-born, -raised and -university educated Deborah Cadman, both highly regarded and highly rewarded.

Before venturing further, it’s worth emphasising how arbitrary this 100 days business is. Good politics for the guy who coined the now gimmicky cliché: US President Franklin Roosevelt in 1932, already New York Governor, campaigning for about the most powerful executive office in the world on the measures required to deal with the Great Depression. But tough for, say, Tees Valley’s Ben Houchen – five opposition years as a Conservative Stockton-on-Tees councillor, and expecting, probably up to election day, to continue running his sporting goods business, rather than a CA comprising entirely Labour-run councils; or Tim Bowles, similarly a backbench councillor in South Gloucestershire, before heading a West of England CA with even less certainty about its identity than the West Midlands.

Moreover, personal experience aside, it’s simply unrealistic to expect in barely three months a substantial record of policy achievement – in a completely new office, with a skeletal organisation, in which personally the incumbents can’t, Trump-like, sign daily executive orders, or indeed actually DO a great deal. One thing, however, they can be expected to do is to staff that skeletal organisation by making top appointments. In the West of England and Liverpool City Region they haven’t, and in their differing ways both seem concerning.

In the West of England, it seems they’re simply slow to emerge from – or possibly even get into – what Mayor Bowles terms ‘start-up mode’. It’s easy – though here, as I’ll suggest, possibly misguided – to question the real-world value of some of the other measures in the table: the ministerial hobnobbing, press releases and suchlike. But to be eating the dust on everything – even the “notable mayoral achievements” were suggested by me! – and still apparently unclear on even your CA’s eventual organisational size, doesn’t look good, either to councillors or an already sceptical public, whom Bowles has already cost over 2p a head.

In the now six-borough Liverpool City Region – as opposed to the fomer five-borough Merseyside Met County Council, which is perhaps part of the issue – the problem seems more obvious. It’s dissent: personal, political and geographical. First, there’s the evidently ongoing power struggle between Liverpool mayor Joe Anderson and metro mayor Steve Rotheram, dating back at least to the latter’s victory over the former in the battle for the metro candidacy. Then there’s the inter-borough stuff, with St Helens most openly but probably others too continuing to question the whole CA-based devolution exercise as “set up to help the cities. The councils who align with Liverpool can control things. The whole concept is flawed.”

The concept’s creator, George Osborne – and no doubt Mayors Rotheram and Burnham – would like Theresa May to revive his Northern Powerhouse project by announcing at either the Conservative Conference or in the Autumn Statement some version of HS3, linking Liverpool to Manchester, Sheffield, Leeds and even Hull. But, with these cities having not one Conservative MP between them, it seems, for this PM, an unlikely priority.

And here those listed ministerial meetings surely do mean something – most obviously that “the ministerial access and contact with senior echelons of government that the mayors have been afforded is more than council leaders and chief executives would normally expect”. And while his defeated Labour opponent Siôn Simon may label Mayor Street as “Tory London’s man in the West Midlands”, in this case it was the Tory Minister who did the calling: Business Secretary Greg Clark, who, in person and in this very university, delivered the Government’s confirmation of a second devolution deal.

In doing so, moreover, Clark kickstarted a policy affecting potentially the whole of English local government that for the previous 12 months seemed almost completely to have stalled. For that reason alone, and with due acknowledgement of Andy Burnham’s adept handling of the aftermath of the Manchester Arena bomb attack, and the other mayors’ early achievements in this artificially short time span, Mayor Andy Street has to be the recipient of my Michael Fish award for just possibly prompting a change in the local government weather.

Chris Game is a Visiting Lecturer at INLOGOV interested in the politics of local government; local elections, electoral reform and other electoral behaviour; party politics; political leadership and management; member-officer relations; central-local relations; use of consumer and opinion research in local government; the modernisation agenda and the implementation of executive local government.