Chris Game

The BBC’s Radio 4 Today programme isn’t what Americans would call a Hot Talk show, and nicely spoken presenter Sarah Montague, even in her own fantasies, is no shock jock. So listeners must have been slightly surprised to hear her, while questioning the proposed devolution of NHS funding to Greater Manchester’s combined authority, talk of “local politicians sticking their grubby hands into the decision-making process” (07.50).

She tried laughing it off and rephrasing, but it was already out there – an unintended confirmation of the dismissiveness with which so much of our London-centric media treat sub-central government. For them, it’s apparently a world too complicated to try to understand and explain; one in which every small service variation is a product not of local democratic choice, or the Lyons Report’s ‘managed difference’ (p.3) – but a ‘postcode lottery’ and thus an easy cue with which to stir up listener and viewer outrage.

With Scotland and Devo Manc putting down serious markers and new combined authorities springing up seemingly every week, English devolution will be a major issue at and following the General Election, whether parties and voters want it or not.

Voters, we know, aren’t clamouring for it. A YouGov/Prospect poll just after last September’s Scottish referendum presented a large sample of English voters with a list of 18 specific things Britain’s government might do over the next few years, and asked them which four or five they felt were the most important.

Probably unsurprisingly, tightening immigration rules came first, favoured by 55%, then providing more money for the NHS and holding down gas/electricity prices. “Giving more powers to English regions and local councils” came 17th, just 12% according it any importance at all. Unpromising, but, unlike England’s cricket World Cup campaign, there are some definite positives out there.

First, as many local authorities used to find when they could still afford to commission annual surveys of residents’ views, councils and councillors generally have a better image, not only than Westminster and Whitehall, but than they themselves sometimes realise.

The Local Government Association (LGA) still does undertake such surveys, its most recent, by Populus last October, broadly confirming previous findings. Around 70% say they’re satisfied with their own council, and, asked who they’d trust most to make decisions about how services are provided in their local area, 72% said councillors, 11% MPs, and 7% government ministers.

But that’s the easy bit. These encouraging levels of satisfaction and trust relate to councils’ currently very constrained tax powers and policy discretion. They quickly dissipate when it’s suggested those powers be extended or more strategic service decisions be made locally.

The YouGov/Prospect poll also asked its English respondents at which level – England-wide, regional, local – decisions on ten services should be made. For six services the choice was overwhelmingly national, including VAT and unemployment benefit rates, the core curriculum, and NHS drug and hospital treatments. Refuse collection frequency was the only decision even a bare majority (53%) allocated to local councils, and 38% wanted even that to be national or regional.

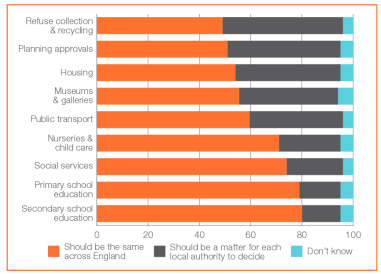

This English predisposition towards uniform national standards in almost everything can seem extreme, but it clearly runs deep and is well documented. A 2012 YouGov survey for the Institute of Public Policy’s Future of England report asked a similar question: whether certain policies should be the same across the whole of England or should be matters for local authorities to decide.

Again, as shown in the chart, there wasn’t a single service – refuse collection, planning approvals, housing, museums and galleries – that a majority of respondents saw as a chiefly local government responsibility.

It’s perfectly possible, even reasonable, to suggest that differently worded questions would elicit different answers; that, if you put respondents in a focus group, presented them with evidence, and let them think for more than five seconds before answering, they’d change their minds; even that, dammit, they’re just wrong. The fact remains that this is what they instinctively think and say, and it presents an unignorable hurdle for would-be devolvers, especially politicians. There are signs, though, that at least the height of the hurdle is adjustable.

Returning to the recent YouGov/Prospect survey, although, refuse collection excepted, there was no service on which respondents came near to preferring local to England-wide decision-making, the picture changed a bit when regional and local preferences were combined.

Put brutally, it’s ‘local councils’ – the label, the actuality, or both – that aren’t trusted with anything more than our rubbish. Combine them with ‘regional level’, and there are clear majorities for the sub-national determination of strategic policing priorities (64%), siting of new towns and major new housing projects (60%), and rules governing social housing rents (52%).

Interestingly, there were some arguably similar findings in the surveys of Londoners and ‘London business decision-makers’ by ComRes in January. In both surveys there were majorities (56% and 60% respectively) in favour of “Local Government having greater control in London over tax levels and how those taxes are spent”.

It quickly turned out that the tax levels most respondents had in mind were limited to business rates and stamp duty land tax. Nor was there anything remotely approaching majority support for even business rates being set by ‘local borough councils’. But again, combine local and ‘regional’ tiers – in this case the boroughs and Greater London Authority/’City Hall’ – and majorities in both samples (58% and 73% respectively) were in favour of ‘Local Government in London’ setting business rates, with over a third in each case prepared to add stamp duty land tax as well.

All of which seems to suggest that, in a future of large, and in some cases almost regional-scale, combined authorities, committed devolvers have at least something positive to work with – provided, of course, media presenters keep their grubby centralist hands out of the debate.

Chris Game is a Visiting Lecturer at INLOGOV interested in the politics of local government; local elections, electoral reform and other electoral behaviour; party politics; political leadership and management; member-officer relations; central-local relations; use of consumer and opinion research in local government; the modernisation agenda and the implementation of executive local government.