Chris Game

I really wish sometimes – OK, occasionally – that I still did my British Government undergraduate lectures. This would be revision season, with lectures atypically well attended, by previously unseen students hoping for hints about exam questions. And there’d be the local elections, and the opportunity to point out once more that, as students, many of them could not only register twice, at home and at their term-time address, but also in these elections vote twice – and try to persuade them to do both at least once.

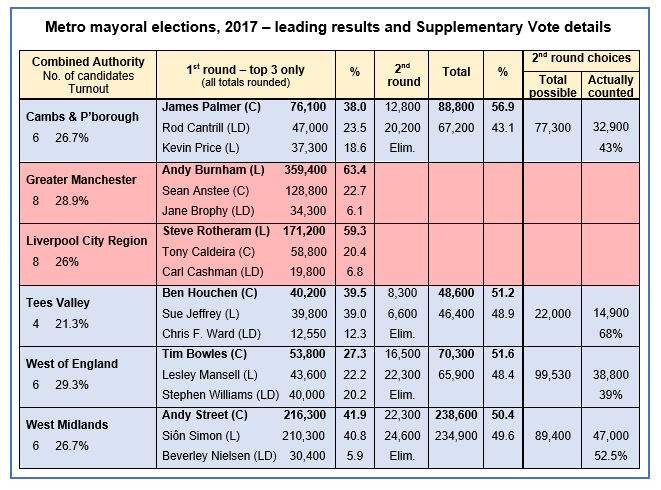

It’s not easy. Post-election opinion polls tell us that in the 2010 General Election, for example, 56% of 18-24 year olds didn’t vote, compared to 35% of all electors and only 24% of over-65s. They don’t usually tell us, though, that most of those 56% couldn’t vote, because they weren’t even registered. The Electoral Commission can, though, and their statistics on the inaccuracy of electoral registers are alarming. Using known population growth rates, the Commission reckoned the April 2011 registers, showing an electorate of around 45 million, were 15% inaccurate, that at least 6 million people in GB were unregistered, and among 17-24 year olds the non-registration rate was 44%.

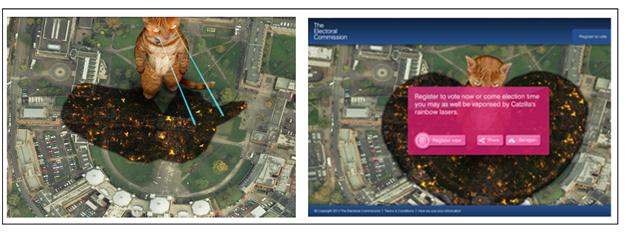

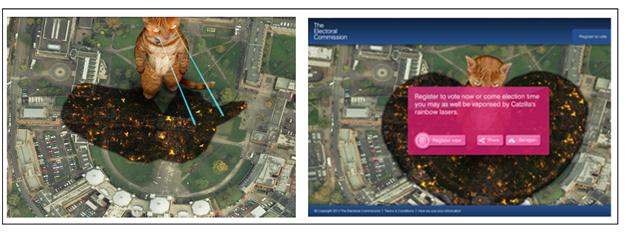

The Commission runs regular campaigns to promote registration, this year’s being clearly aimed at these elusive young people. I’m not sure about its effectiveness, but I’d certainly use it, and I can recall few visual aids of whose student appeal I would be more confident. ItsYourVote is a website whose home page comprises a satellite image of the UK, and a warning that “Without a vote, you have no say in what happens in your local area”. To learn what fearful fate that might be, you enter your postcode, whereupon the satellite homes in and you discover that, should you fail to register, “come election time, you may as well be vaporised by Catzilla’s rainbow laser eyes”, or possibly seized by a massive disco fairground grabber, or swept up by a giant ice cream scoop.

Source: ItsYourVote

The Daily Mail thinks the website “absurd” and an appalling waste of public money. But I fear it misses the subtlety. While obviously the ice cream scoop is a bit silly, you can see that Catzilla, though provoked by the under-registration of Birmingham University students, has been impressively selective in his vaporisation of our Edgbaston campus – wiping out the Law faculty and the entire University administration, but leaving untouched, for instance, the Muirhead Tower and my civic-savvy, fully registered INLOGOV colleagues.

As it happens, the Commission’s efforts would be wasted on most of our students this year, for, as noted in my elections preview blog, this is the one year in four when the metropolitan boroughs like Birmingham, along with most unitary authorities and shire districts, don’t elect any of their councillors. This leaves just 37 councils in England plus one in Wales holding any kind of local elections this week, and, with that first blog having at least briefly covered those in the 8 unitaries and the mayoral elections in Doncaster and North Tyneside, the remainder of this one will focus on the 27 county councils.

They were previously elected in 2009, when Labour’s standing in the opinion polls was desperate – 16% behind the Conservatives, at 23% to 39%, with the Liberal Democrats on 19%. Reflecting those figures, the Conservatives, the dominant party anyway in this tier of local government, won nearly nine times as many seats as Labour – 1,261 to 145, with the Lib Dems taking 346 – and took majority control of every one of the 27 councils except Cumbria, where they became the leading party in a Conservative/Labour/Independent coalition.

2009 is therefore the baseline against which to assess the prospects and eventual performance of the various political parties, whose standings in the polls today are, of course, dramatically different. In this week’s Sunday Times YouGov poll, Labour have a 9% lead (40% to 31%) over the Conservatives, with the Lib Dems and UK Independence Party (UKIP) level on 11%, and the Greens on 3%. These figures indicate a Conservative –> Labour swing of nearly 13% since 2009, and no swing at all between the Conservatives and Lib Dems. It’s a blunt measure, but about the best we have for assessing the electoral chances of the major parties.

In the same poll, incidentally, UKIP leader, Nigel Farage, gets a higher rating as a party leader – 44% saying he’s doing a good job – than Cameron (36%), Ed Miliband (29%), or Nick Clegg (21%). Partly because of headlineable findings like these, and partly because they are a real, but unpredictable, threat to all parties in these elections, UKIP have, as Karin Bottom noted last week, been attracting the bulk of media attention. In terms of seats, though not councils, gained, they will undoubtedly be among Friday’s winners – indeed, it’s about the one knowable thing about them – but mainly because they’ve virtually nothing to lose.

UKIP like boasting of their “army of councillors sitting on borough, town, county and parish councils across the UK”. This army, though, would make Gideon’s little band of soldiers that took on the Midianites seem like a legion. In fact, its massed ranks contain just over 100 town and parish councillors (out of 75,000) and about 30 on principal authorities – including 11 (out of 1,800+) on county councils. And there’s a similar economy with the truth in its manifesto claim that “where UKIP is in charge of local government, we use that power to cut costs … we believe that council taxes should go down, not up”. Back on Earth, the only local government of which UKIP has ever had charge is Ramsey Town Council in Huntingdonshire, Cambs., and since taking ‘power’ in 2011 they have ‘slashed’ the council tax precept by +28%, from £42.56 on Band D to £54.61 in 2012-13.

Council tax rates are, quite properly, a big issue in these elections, but hardly a straightforward one. First, Coalition Government ministers have from the outset done their utmost to set – that is, freeze – all councils’ tax and spending totals themselves, by bribing them with limited and potentially disadvantageous freeze grants. Second, it is the districts, not the county councils being elected this week, who are the billing authorities who will have sent out the bills and be trying to collect the taxes, even though it’s the counties who do about 90% of the actual spending.

Third, this year, although almost all counties obediently accepted their one-off grant deals and froze their tax precepts, well over a third of the districts refused them and raised their tax bills – more than half of whom were Conservative-controlled. So, does a voter in one of these ‘naughty’ districts, urged by David Cameron to vote Conservative for lower council taxes, punish the council that raised its tax or reward the county that didn’t?

It’s nothing like as simple as, for instance, street-lighting. It’s not, perhaps surprisingly, a statutory obligation for any council, but, if your street lights are being dimmed or switched off in the interests of economy, it’s almost certainly the county who control the photo-electric timers. So, either way, if you approve of the cost and carbon savings, or disapprove of jeopardising safety and security, you know how to vote.

So how many of the 27 counties, all Conservative today, will be differently controlled come Friday? In Cumbria, the one that half got away in 2009, Labour in recent years has usually had a plurality, if rarely a majority, and will be looking to regain that position of largest single party. However, a Conservative Police and Crime Commissioner (PCC) was elected in November, and, as elsewhere, Ed Miliband’s claim to be “fighting for every vote” is undermined by the party fielding 14 fewer candidates than in 2009, while Greens are up from 15 to 31, UKIP from 4 to 52, and, in another sign of the times, the British National Party (BNP) down from 41 to 9.

While becoming largest party may be fine in Cumbria, in the four councils Labour held virtually uninterruptedly from 1981 until 2005, anything short of winning back majority control will surely count as failure. Derbyshire was numerically the Conservatives’ narrowest capture, with 33 of the council’s 64 seats, and they have already lost that overall majority, with one councillor having to resign for unsavoury personal reasons and another switching allegiance to UKIP. Even a modest swing should do. Nottinghamshire is much trickier, for in 2009 Labour lost seats variously to the Conservatives, the Lib Dems, UKIP (in Ashfield), and assorted Independents, especially in Mansfield. A straight swing of even 10% from the Conservatives might not be enough, but a repeat of those with which they won by-elections in Worksop and Rufford certainly would. In Lancashire too Labour need almost to reverse the trouncing they suffered at the hands of all parties, including the Greens and BNP. A 5% swing from the Lib Dems in Burnley, where they have already won back one seat in a by-election, and a 10% swing from the Conservatives elsewhere should do it – even without ousting the notoriously independent Idle Toad, Tom Sharratt, from his South Ribble fastness.

If Lancashire was a trouncing, Staffordshire was a bloodbath, from which Labour crawled out with just 3 of its former 32 seats. With nearly two-thirds of divisional boundaries having been changed, it is difficult even to assess the scale of the task of regaining majority control from such a tiny base, the most promising guide being perhaps the results in the three districts that held elections last year. In both Cannock Chase and Newcastle-under-Lyme Labour took majority control of the council by gaining a total of 15 seats from the Conservatives, Lib Dems, and in Newcastle also from UKIP. In Tamworth too they won seats from the Conservatives, and across the three councils there was an average Conservative –> Labour swing since 2009 of 14%, which, repeated on Thursday, would indeed have been sufficient, without boundary changes, for Labour to reverse the horrors of 2009. In November, on the other hand, the electorate – or a very small portion of them – preferred a Conservative PCC.

Had the Lib Dems gone into opposition in 2010, rather than national coalition, they too would be aiming to regain the councils they lost in 2009: Somerset, Devon and, although it became a single-county unitary at the same time, Cornwall. But two years of depressing opinion polls and local election results are taking their toll, and Devon, for example, seems to be one of several counties in which UKIP candidates will outnumber Lib Dems. Indeed, Ilfracombe, in Lib Dem hands for years, appears to be being surrendered without even a defence.

Somerset, where almost all contests are between the Conservatives and Lib Dems, and the latter were in majority control for most of the period between 1993 and 2009, is a much stronger prospect. Again, extensive boundary changes make projections difficult, but even a 5% Conservative –> Lib Dem swing on existing boundaries would be enough for the Lib Dems to regain control. But, as noted above, there’s been no perceptible swing at all, and the easy victory of an Independent in the Avon & Somerset PCC election may suggest that this is particularly promising territory for independents and smaller parties.

As for the rest, it might seem that in these uncertain times, if a case can be made for Staffordshire being recoverable by Labour from a councillor base of three, almost anything is possible. Well, yes – but realistically, even a really good result for Labour would probably be limited to depriving the Conservatives of their overall control in a few more councils. One could be Warwickshire, which, as a minority administration Labour have run for longer in recent years than have the Conservatives, and another Northamptonshire, one of apparently a small handful who are all claiming to have “the lowest council tax set by any of the 27 shire counties in England”.

Clearly they can’t all be right, and, this being an academic blog, I feel it’s appropriately pedantic to close by citing the relevant House of Commons note reporting that Northamptonshire’s Band D equivalent precept of £1,028.11 is in fact only third lowest, behind Staffordshire (£1,027.25) and Somerset (£1,027.30).

Chris is a Visiting Lecturer at INLOGOV interested in the politics of local government; local elections, electoral reform and other electoral behaviour; party politics; political leadership and management; member-officer relations; central-local relations; use of consumer and opinion research in local government; the modernisation agenda and the implementation of executive local government.