[This post, incorporating the final results, was updated by the author on 5th June 2013]

Chris Game

In May 2010 David Cameron and Nick Clegg took just five days to form their national coalition. By contrast, starting in June 2010, the Belgians took 18 months to form theirs. English local government falls between the two.

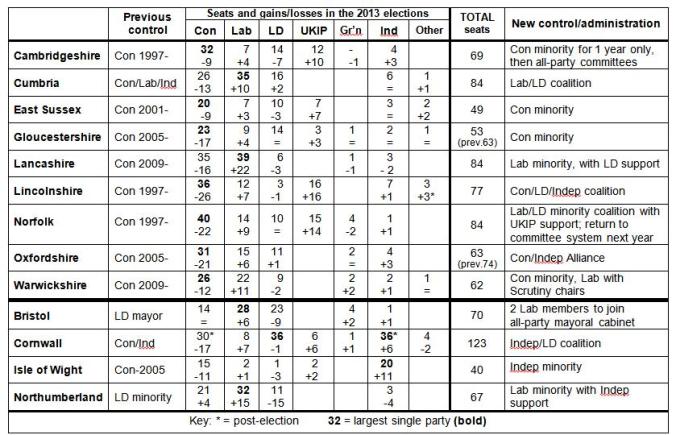

It’s well over a month now since the national media completed their coverage of the local elections. They’d added up the seats won and lost by the various parties, calculated the national vote share they’d have received if the elections had been held in different parts of the country, and how many seats they’d have won in a 2015 General Election – but they left as unfinished business the 13 county and unitary councils they conveniently lumped together in their tables as ‘NOC’ (No Overall Control). And, though it was a short sprint by Belgian standards, it took most of that month for most of us to learn, in several of these 13 cases, the answer to that basic question the elections were supposedly about: who will actually govern?

The reasons are various: more parties, plus variegated independents, involved in negotiations; party leaders losing their own seats, or having to be re-elected or deposed at party meetings; and, above all, the fact that any inter-party agreements can only be officially implemented at pre-scheduled Annual Council Meetings, which, in some of the affected councils, only took place in the last week of May.

This blog attempts to fill in the gaps. It’s a kind of ‘runners and riders’ guide to the 13 county and unitary councils in which no single party has a majority of seats: how they got that way, and what subsequently happened.

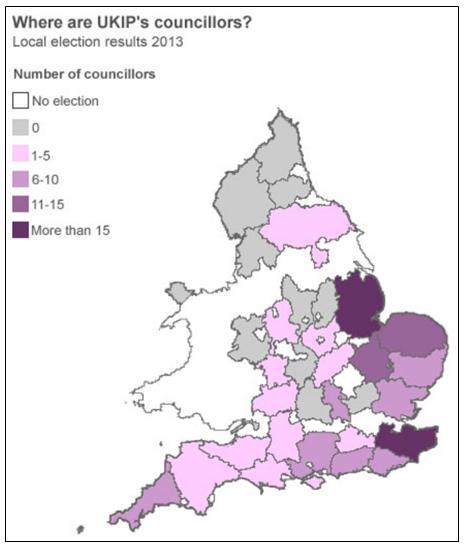

First, the counties, in alphabetical order. CAMBRIDGESHIRE, along with Lincolnshire, Norfolk, and to a lesser extent East Sussex, was one of the previously staunchly Conservative counties that became hung largely as a result of being UKIPped. As the BBC map shows, this was a much patchier experience than was suggested by some commentators at the time – with 7 of the 27 counties still having no UKIP councillors at all and only 4, all in the south and east, having more than 10.

Source: BBC News

The Conservative leader, Nick Clarke, was one of those who lost his seat to UKIP, and the party’s remaining 32 seats left them well short of a majority. The new leader, Martin Curtis, wanted to go it alone as a minority administration, but the Independents ruled that out, while Labour and the Lib Dems refused to join UKIP in supporting an Independent-led non-Conservative rainbow coalition. Eventually, the Conservatives got half their cake: Curtis will head a minority administration for 12 months, but then UKIP’s preference, for ‘opening up’ council decision-making, kicks in and cabinets will be replaced by all-party committees.

In CUMBRIA, previously run by a Con/Lab/Independent coalition, the elections effectively reversed the standings of the Conservatives and Labour, with the latter regaining their customary position as largest party, and the slightly strengthened Lib Dems in the role of potential kingmakers. Under a new leader, Jonathan Stephenson, they opted for coalition with Labour, deputy leadership of the council, and four cabinet posts.

EAST SUSSEX is a much smaller council than Cambridgeshire, but proportionately the party arithmetic is broadly similar. Here, though, the other parties seem readier to accept a Conservative minority administration, and, as in Cambridgeshire, although a Conservative-UKIP deal could have produced a majority, none appears to have been seriously pursued.

GLOUCESTERSHIRE was a hung three-party council from 1981 to 2005, with Lib Dems generally the largest group – before, in 2009, the Conservatives suddenly took 42 of the then 63 council seats. The reduction of 10 seats, accompanying boundary changes, and the prospect of at least some recovery by Labour and possibly the Lib Dems led close observers to predict a return to NOC, and they were right. The Conservatives, though, will continue in office as a minority administration, and the Lib Dems as the main opposition party, miffed reportedly at a suspected Con-Lab deal over Scrutiny Management and other committee chairs.

Meanwhile, the county’s badgers, temporarily reprieved last autumn from the Government’s planned cull, seem to have lobbied with some effect in the elections, the new council voting by 25 to 20 with 7 abstentions to oppose the cull, now due to start later this month.

In LANCASHIRE Labour either controlled the council or were the largest party from 1981 until 2009, and were hoping to regain majority control in one go. Sensing a lifeline, the Conservatives tried talking with anyone who might be interested in forming what would presumably be an anti-Labour coalition. But the Independents didn’t want an alliance with anyone and in the end the Lib Dems agreed to support a Labour minority administration – support that will include Labour’s budget, but not necessarily much more.

LINCOLNSHIRE Conservatives are unused to coalition politics, but the party’s leadership reacted quickly to the loss of nearly half its seats by negotiating a coalition deal with the Lib Dems and Independents, before the 16 new UKIP members could even elect themselves a leader. In the week they spent doing so, the party’s regional chairman pooh-poohed on their behalf any coalition with the Conservatives, and effectively condemned them to opposition from a starting point that might have yielded rather more. The Lincolnshire Independents group were also outsmarted – three of their number breaking away to join the coalition, one with a seat in the cabinet, with rumours that others could follow them into what is still a group-with-no-name.

Across The Wash, in equally traditionally Conservative NORFOLK, the outmanoeuvred group were the Conservatives themselves. At a full council meeting, the party’s re-elected leader, Bill Borrett, apparently thought he had an agreement with the Lib Dems at least to abstain in any vote, thereby enabling him to head a minority Conservative administration. He hadn’t, and nor was he able to nail down a more explicit coalition agreement with the Lib Dems involving some key specified posts. By far the largest group thus finds itself in opposition to a minority coalition of Labour and the Lib Dems based on just 29% of council members.

UKIP’s 15 votes were needed to get this deal off the ground – plus support from the Greens and an Independent – and the UKIP group describes itself as part of the coalition. That part, though, involves no cabinet seats, but rather the achievement of a Cambridgeshire-style agreement to abolish cabinet government and return to a committee system this time next year.

Before the Conservatives swept into power in 2005, OXFORDSHIRE had been a hung council for 20 years. Labour’s comeback was limited, and, on a now a significantly smaller council, the Conservatives finished within one seat of retaining their overall majority – a position they’ve restored thanks to a CIA: a Conservative/Independent Alliance probably less alarming than it initially sounds. No cabinet seats are involved, but three Independents have agreed to work with a Conservative minority administration in the kind of ‘confidence and supply’ arrangement that many thought was as far as Cameron and Clegg would dare to go in 2010, and indeed to which they may still, before 2015, conceivably turn.

In WARWICKSHIRE Labour, though never the majority party, have regularly run the council as a minority and were hoping to regain this position. They didn’t, but they did do a deal with the Conservatives, the outcome being a Conservative minority administration, headed by the council’s first woman leader, Izzy Seccombe, with Labour holding the Scrutiny chairs, and the Lib Dems and Greens out in the cold, complaining of a stitch-up.

Now to the four hung unitaries. In BRISTOL Labour became again the largest single party and has agreed that two of its members should join Mayor George Ferguson’s all-party cabinet, which will now comprise 2 Labour members, 2 Lib Dems, I Conservative, and I Green. That may sound straightforward, but it most certainly wasn’t. Last November a similar proposal, though supported by Labour councillors, was overruled by the local party and eventually by the National Executive, and had cost the group its leader, Peter Hammond. It seems a sensible decision, but it would be surprising if that sentiment were shared universally within Labour circles.

In CORNWALL, as in Lincolnshire, some candidates continue running around long after the electoral music has stopped. Here, one of the elected Conservative members defected after 10 days to the Independents, bringing the latter group up to parity with the Lib Dems. This proved, though, less crucial than it might have, as both groups were already in discussions over some form of agreement – one possibility being an all- or multi-party rainbow alliance that could be presented to the public as a ‘Partnership for Cornwall’. What actually emerged was more mundane: an Independent/Lib Dem coalition with the more or less positive support of Labour, UKIP and Mebyon Kernow (the Party for Cornwall), the Conservatives having rejected as tokenism a scaled-back offer of two cabinet seats.

The ISLE OF WIGHT was once a Lib Dem showcase, controlled by the party either as a majority or in coalition for 16 years until 2005. It seems like history now, though, and this year’s election was largely about the exchange of seats between the Conservatives and Independents – the latter at least slightly helped by Labour and UKIP not contesting every seat that they might have done. The Island Independents, led by Ian Stephens, one of the possible beneficiaries of these arrangements, took over as easily the largest group, and will run the council as a minority administration – for the first time since 1973-77.

Having dominated the former county council, Labour will run unitary NORTHUMBERLAND for the first time as a minority administration, with the support of the three Independents – one of whom will be back as Chairman of Audit, the post she held as a Conservative councillor before resigning from the party following alleged victimisation by a senior colleague. And to think, there are some who say the local government world is boring.

Chris is a Visiting Lecturer at INLOGOV interested in the politics of local government; local elections, electoral reform and other electoral behaviour; party politics; political leadership and management; member-officer relations; central-local relations; use of consumer and opinion research in local government; the modernisation agenda and the implementation of executive local government.