Martin Stott

The Poll Tax riots in 1990 famously brought down Mrs Thatcher and led to the hasty introduction of the Council Tax. Twenty three years later are the reforms to Council Tax (due for implementation in less than a month) about to bring the Poll Tax back from the grave?

From 1 April, instead of the current 5.9 million recipients of Council Tax Benefit (CTB) receiving cash to cover all or most of their bill, as part of the Government’s policy to roll back and cut the cost of the welfare state the fund for CBT will be cut by 10%. At the same time the Government has localised the system, transferring responsibility for it from Government to the 326 local authorities responsible for Council Tax collection.

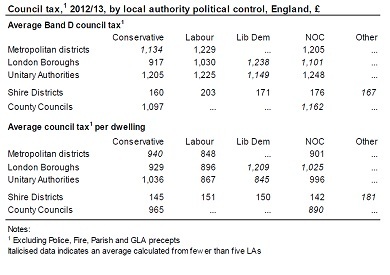

From April, in order to balance their budgets, councils will be faced with maintaining current levels of support and making greater cuts elsewhere, removing other exemptions. The most commonly cited is Council Tax (CT) exemption on second homes, or asking those who currently don’t pay CT or only pay a very small amount, to pay. As the date for this change looms, it seems that the vast majority of councils will opt for the latter. The calculations are made particularly tricky by the Government’s stipulation that current levels of support must be maintained for pensioners – meaning that the burden will fall entirely on the working-age poor.

The Resolution Foundation has published a report setting out exactly what all this means. If you are poor and not a pensioner, it doesn’t look pretty. Just as important though, if you are a local authority, especially one with quite a few claimants and not many second homes to tax, the financial implications look terrifying.

With 5.9 million recipients, Council Tax Benefit is claimed by more households than any other means tested benefit or tax credit. On 1 April it will be replaced by 326 ‘Council Tax Support Schemes’. The Resolution Foundation report shows that almost three quarters of English local authorities are planning to respond to this localisation by introducing less generous systems of support.

For individuals and their families the implications of this are huge. The effect of this new localisation of council tax support will see many of the 2.5 million working-age recipients of CTB who are not in employment, i.e. those who receive maximum CTB and pay no council tax, having to pay something. Depending on the wealth of the locality they live in and importantly the number of exempt pensioners, the figures are likely to vary between £100 and over £300 per annum with an average of £247pa. North Hertfordshire has already announced a figure of £322.40 pa and Birmingham, Britain’s biggest local authority, has announced a minimum charge of £200 pa. One of the reasons for the variation is the exclusion of pensioners from the charges. This immediately increases the apparently marginal 10% to an average 19% reduction for working age recipients, and in some areas with high proportions of pensioners this rises to 33%.

This is all in a context where Universal Credit is introduced in October with as yet unknown implications, but with a computer system that probably isn’t up to the job; benefits increases capped at 1% pa for the next three years – a real terms cut; the ‘bedroom tax’ just about to kick in and food banks springing up all over the country. Figures from the Institute of Fiscal Studies reported in the Resolution Foundation report show that the average working family will lose £165 pa from these changes and the average non-working family will lose £215pa. It doesn’t take a genius to see that this combination of pressures will have huge impacts on low income families and individuals, and that paying Council Tax won’t be anywhere near their top priority.

The implications for local authorities and their finances are almost as stark as those of individuals. While the average of £247pa sounds, and is, a lot for poor households, collecting £4.75 a week is likely to prove uneconomic for local authorities, especially if collection attempts go as far as hiring bailiffs or going to court. Work by the campaign group False Economy has found that more than 70 councils are resigned to seeing swaths of residents refusing to pay the tax. Harlow council is expecting to get barely one sixth of its 5,000 poor households paying up and is budgeting for a £1.14m shortfall in its finances in 2013/14. Gravesham is expecting only a 30% payment rate. Most councils are more optimistic, but the False Economy work suggests that overall, councils are expecting one third of those who are supposed to pay, won’t.

Ministers are planning to save £500m by cutting and localising the CTB bill. But even Conservative former ministers are sounding alarm bells. Patrick Jenkin, a key architect of the poll Tax, told the BBC last year:

‘The Poll Tax was introduced with the proposition that everybody should pay something….. we got it wrong. The same factor will apply here, that there will be large numbers of fairly poor households who have hitherto been protected from Council tax who are going to be asked to pay small sums’.

Faced between the choice of heating their homes (ever more expensively), feeding their families, or paying £247 per annum in Council Tax, which is likely to go first? In trying to save £500m a year, the new arrangements look like causing huge financial problems for many councils and bad publicity for Government as these councils try to chase non-payers through the courts, that only that kind of money can buy. Welcome to the New Poll Tax.

Martin Stott has been an INLOGOV Associate since 2012. He joined INLOGOV after a 25 year career in local government, both as an elected member and as a senior officer.