Chris Game

Local elections present the INLOGOV blog with an annual dilemma. They’re the heartbeat of democratic local government, its lifeblood, or something equally vital. So, they must be covered and key results namechecked. But INLOGOV’s not a news service, and, with so many Friday counts nowadays and results instantly available on social media, you have somehow to strike a balance.

The first part of this blog, therefore, will give the headlines, from a strictly local government perspective. That means, first, changes in council control; second, changes in councillor numbers; and third, excluding one minor indulgence, no conjecturing whatever about implications for that other election.

Conservatives, of course, were the big winners, almost everywhere. So, to be perverse, we’ll start with a titbit of consolatory Labour news, from the seven unitary polls. Durham it still controls, and Northumberland – thanks to the Conservative candidate in the potentially decisive ward literally picking the short straw – stays technically hung, though no longer under Labour minority control. After mass gains from particularly Independents, Conservatives are the largest party in Cornwall and back in control in the Isle of Wight.

Of the 27 non-metropolitan counties, even before last Thursday Labour had majority control in only Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire, and shared minority control in Cumbria and Lancashire. Conservatives are now in control of the first and last of these and are easily the largest party in the other two. Cambridgeshire, East Sussex, Gloucestershire, Lincolnshire, Norfolk, Oxfordshire, Suffolk and Warwickshire all swung from minority to majority Conservative control.

As was widely, and even gleefully, reported, UKIP too lost heavily, its single gain in Lancashire being rather more than counterbalanced by at least double-figure losses in Cambridgeshire, Kent, Lincolnshire, Norfolk, Suffolk and West Sussex.

Turning to overall councillor numbers, the Conservatives gained what for a party in national government was an almost mind-boggling 563 seats: 319 in England, 164 in Scotland, far more than doubling their previous representation, and 80 in Wales – the latter, according to more knowledgeable commentators than I, putting the party on course (in that election I’m not mentioning) for its first nationwide Welsh victory since the Earl of Derby managed it in 1859.

Labour’s car crash involved losing net 382 councillors – bringing to 15 years the period since, in terms of councillor numbers, it was the largest party in GB local government – UKIP 145, and the Liberal Democrats what must have been a deeply dispiriting 42.

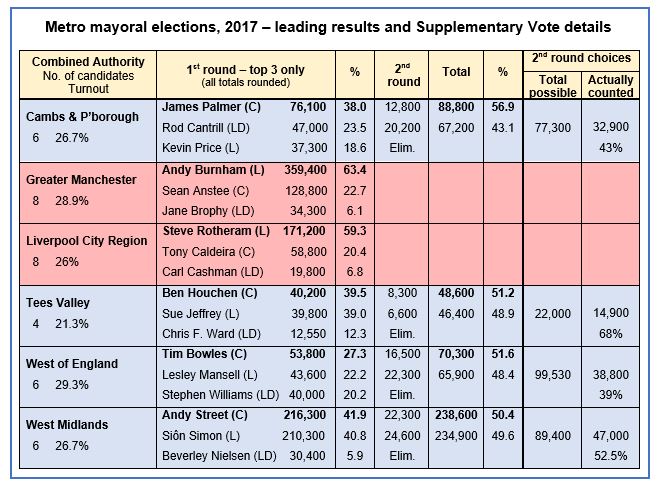

And so to what, for the immediate future of at least England’s sub-national government, were surely last week’s most important elections, and collectively way up there amongst the most mind-boggling: those of our first(?) six metro mayors. I can hardly imagine the odds you could have got, even a week ago, on four of the six being Conservative. However, it’s there in my table, in blue and pink. And, whatever one’s reservations about elected mayors and the whole limited, top-down, Treasury-driven, fiscally minimal devolution model, I’d suggest that nothing over the past 11 months has given it a greater boost.

The first several months of May’s premiership she spent almost visibly dithering over what to do about the severed agenda of devo deals and elected mayors she’d inherited from the axed George Osborne and shuffled ex-Communities Secretary, Greg Clark. Then – I simplify enormously – two things happened.

First, Andy Street decided he’d stop being MD of the John Lewis Partnership and run as a Conservative for the biggest and politically most attractive metro mayoralty of all, the West Mids – in time to be adopted, and then paraded with May at the party’s October Birmingham conference.

At the same time, something else helped change her view that one big reason why metro mayors were a bad idea was that most, if not all, would be Labour. Several of Clark’s nine envisaged metro-mayoral city regions, during the May-created devo vacuum, started for various reasons to lose interest or patience and drop out – West Yorkshire, Sheffield City Region, the North East – and the political arithmetic began to alter. To the extent that I suggested she could realistically conceive of the first set of mayoral elections producing three Conservative and three Labour mayors. Even for the sake of an eye-catching headline, though, I’d never have contemplated 4-2.

And, as the table shows, three of the four results, after the two counts involved in the Supplementary Vote (SV) electoral system, were extremely close. Street’s majority was exceptionally so – 0.71979% of over half a million votes cast, to be precise. This in itself would weaken any victor’s mandate, particularly when achieved in what, by the standards of anything other than Police and Crime Commissioner ballots, were very low-turnout elections.

The SV system was adopted for mayoral elections almost by accident, and many consider that the more familiar Alternative Vote – that we rejected for parliamentary elections in the 2011 referendum – would be fitter for this particular purpose. Its defenders, though, claim it has worked well in London, is voter-friendly, produces clear winners, and is accepted by all concerned.

My table would suggest otherwise, at least on its first showing. In the West Midlands, in a hugely significant election decided by well under 4,000 votes, over 40,000 votes that might have contributed to the result didn’t do so. They were either not used at all, or were cast for candidates who, highly predictably in this instance, had already been eliminated after the first count.

It’s impossible to avoid the conclusion that large numbers even of the small minority who turned out didn’t fully comprehend the system they were voting in – for which the Electoral Commission must be held chiefly responsible. As also for the huge disparities in candidate expenditure permitted before the ‘regulated’ campaign period, which again in such a closely run race can and will be alleged to have been decisive. In short, the Commission, as well as the mayors themselves, have plenty of work to do in what is only a three-year term to 2020.

Chris Game is a Visiting Lecturer at INLOGOV interested in the politics of local government; local elections, electoral reform and other electoral behaviour; party politics; political leadership and management; member-officer relations; central-local relations; use of consumer and opinion research in local government; the modernisation agenda and the implementation of executive local government.