Dr. Max Lemprière & Professor Vivien Lowndes

If you’re a local authority leader today you will doubtless be considering opportunities to gain devolved powers and funding from central government as part of a Combined Authority (CA) deal. Or perhaps you are already part of the joint leadership of a new Combined Authority (CA)? Since the emergence of the Greater Manchester Combined Authority in 2011, a further nine have been formed, with eight in total holding elections for directly elected mayors. New deals are in the pipeline, and those who have yet to strike one fear being left behind.

We’ve spent the last few years following these developments, asking what their emergence tells us about the nature of devolution and central-local relations. We’ve highlighted the role of well-defined leadership, existing institutional structures that favour joint working, and a range of locally specific factors, like shared identities and partnership culture.

But what is also clear is that English devolution policy is constantly evolving, responding to (and seeking to capitalise upon) broader political and economic trends. It is that which we want to discuss here.

CAs are voluntary collaborations between elected local authorities in England that have received devolved powers and funding from central government to support infrastructure and economic development, on the basis of negotiated settlements. Since 2010, central government has championed CAs as a vehicle for stimulating regional economic growth and rebalancing the economy away from London and the South East. They vary in terms of their powers, funding, priorities and governance. New CAs have been formed at different points since 2010, and are working to different deadlines for performance reporting to central government and negotiating follow-on packages of additional funding and devolved powers

We have argued elsewhere that the devolution policy underpinning CAs represents a noticeable shift in central-local relations. Rather than imposing a ‘one-size-fits-all’ model of devolution, the policy has been based upon bespoke negotiated agreements between groups of local authorities and Whitehall. The policy is also morphing in response to developments in Westminster and beyond.

The most significant developments are the arrival of Boris Johnson as prime minister, in the context of the 2019 Conservative landslide, and the ongoing Brexit agenda.

What these highlight is that the political saliency of the CA agenda varies depending on the will of political leadership at the national level and their existing policy priorities. What’s more, they show that, as CAs become more empowered and begin to bed-in and develop trajectories and momentum of their own, a tussle emerges between the CA and national level, particularly in the on-going battle for a further devolution of powers and funding. For example, the Greater Manchester CA has made vocal appeals for repatriated powers and funding over transport and skills training to land at the regional rather than national level.

Boris Johnson is a former directly elected mayor of London. In the 2019 general election, he based his claims to be able to ‘get things done’ as PM on his record at London mayor. Johnson’s power and influence in that role, and personal visibility, owed everything to New Labour’s devolution policy, which had created the mayorality and Greater London Assembly in 2000. He has now promised to ‘do devolution properly’, signalling an opportunity for existing CAs to expand their capacity and influence, especially in the North of England. Many CAs represent areas in the former ‘Red Wall’, where support for Labour crumbled and voters ‘lent’ their support to Johnson’s Conservatives. Now, many see an opportunity to call in the favour and make demands for further devolution.

Overshadowing all of this is Brexit. Voters in these regions shifted their allegiance towards the Conservative Party in order to ‘get Brexit done’, but Brexit itself presents opportunities and potential pitfalls for existing and proposed CAs. Many see an opportunity emerging for CAs (rather than Whitehall) to claim some of the powers being repatriated to Britain. Could Brexit lead to regions ‘taking back control’ as well as the national government? Johnson’s premiership represents a critical juncture for the devolution policy, which had stalled between 2016-19 in the face of struggles over Brexit, and an ideal opportunity for regional leaders to strengthen their calls for further powers

Johnson is on record as supporting the CA agenda. New CAs are currently being negotiated with the Treasury (for example in Yorkshire and Lancashire), and Johnson has advocated for further devolution of funding and powers to existing CAs, particularly over transport and infrastructure, in line with his government’s broader domestic agenda. The commitment to a Northern Powerhouse Rail programme suggests the agenda may be gaining traction. Regional leaders are hoping that Johnson has learnt about the benefits of locally controlled infrastructure from his experience at the helm of the most well developed regional transport body, Transport for London.

This new breath of life for the devolution policy follows a period of uncertainty following the departure of Chancellor George Osborne in 2016. Under David Cameron’s government, Osborne had been the architect of the CA agenda, personally pushing the agenda and getting the deals signed off the deals. Following the Brexit referendum, Theresa May’s government let the devolution policy flounder, preoccupied with the fall-out from the ‘leave’ vote.

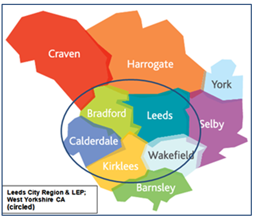

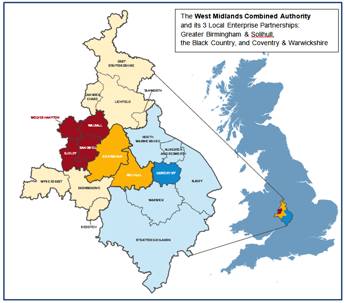

The CA agenda may well be gaining new traction, as a result of both bottom-up and top-down demands. Recent years have seen many success stories, from the Greater Manchester poster-child, to ongoing negotiations with Lancashire, to further rounds of devolution for some of the UKs biggest cities. As time goes on, CAs are likely to gain the confidence they need to challenge central government in the on-going tit-for-tat that has characterises UK central-local relations. This isn’t to say that there haven’t been failures; our own research for example has shown how the North East Combined Authority failed to negotiate a meaningful devolution package with central government due to poorly constructed economic and political geographies and a lack of congruence or leadership. Having said that, a new North of Tyne Combined Authority has arisen from its ashes and negotiated a successful deal with central government.

But this also points to the way that CAs will continue to evolve in the future. Brexit was, to some extent, a product of social division, and a distrust amongst those at the local level about politics and priorities driven by Westminster and Whitehall. Beyond London and the South East there was a particularly powerful distrust of elites and a feeling among many that they had been ‘left behind’ by the dominant economic model. Indeed, the CA agenda itself was an attempt to alleviate growing regional discontent in England in the aftermath of New Labour’s devolution to the Scottish government and Welsh. Renewing the CA policy provides an opportunity to decentralize responses to the demand to ‘take back control’. English devolution has the potential to rebalance the economy whilst also reducing social division and mistrust in Westminster politics.

It remains to be seen whether combined authorities are able to capitalise on these opportunities, and indeed whether Westminster is serious about pursuing them. What we also need to watch out for is whether it is only those existing CAs, which have already proved themselves to be adept at bidding for power and funding (Greater Manchester and the West Midlands come to mind), that will be able to win the tussle for extra post-Brexit powers, or whether the bounty will be shared more evenly. The danger is, of course, that what is already seen by some as an uneven distribution of powers and funding away from Westminster will be aggravated further.

Max Lempriere is an Associate at INLOGOV. His research interests lie in local governance, institutions, sustainable development and urban planning. He completed a PhD in the politics of sustainable urban development.

Vivien Lowndes is Professor of Public Policy at INLOGOV. She undertakes research, teaching and knowledge transfer on local governance, political institutions, citizen participation, gender and migration. Professor Lowndes is Chair of the Politics and International Studies Sub-Panel for REF 2021, the UK’s periodic assessment of research quality.