Marc Greenwood

This week we are showcasing key findings from some recent dissertations by our Degree Apprentices. This dissertation identifies the barriers to and the motivations for digital adoption in adult social care services. By exploring the impact of governance approaches and leadership styles in influencing the adoption of digital technologies in the home, it identifies techniques and approaches for supporting social care services to accelerate and sustain digital adoption.

Key findings:

- Care technology in the home needs to become part of the standard way of operating within adult social care. By doing so it is possible to de-mystify care technology, helping to normalise it, thereby increasing adoption.

- Help stakeholders become more aware of the possibilities associated with care technology.

- Develop the skills and confidence of professionals, carers and users: if people feel confident they are more likely to use the technology, and the reverse is true if they have low skills and confidence.

- Limitations to digital adoption, due to economic and geographical reasons, are a consistent barrier.

- Leaders are key to successful adoption. Leaders need to immerse themselves in the change. This includes using the technology themselves and not underselling the value their own behaviours have in influencing others to adopt technology in adult social care.

- Leaders need to have a strong vision for change and develop a shared narrative that followers could understand and engage with.

- Leaders must empower others to deliver the digital adoption agenda by allowing them to try new things, and to accept that sometimes things will fail.

- The skill of a leader to learn and adapt their approach is key – leaders must learn from what has worked well and what hasn’t.

- Build networks and partnerships with effective dialogue influencing the work and direction of the network. De-risk digital adoption initiatives through collaboration and risk sharing.

- Engage with users of services to understand what they want and what works for them. This way there is the possibility of greater adoption of digital services through shared ownership and buy in.

- The role of place level governance is one that has the potential to influence the impact of digital adoption across networks through shared ownership and accountability.

Background

The development of digital technologies in adult social care has progressed significantly in recent years with the potential to transform the public sector landscape. From traditional telecare services, through to remote assessment collaboration tools and independent living applications, the scale and scope of technology is burgeoning. The Covid pandemic expanded and accelerated these innovations. There remain however social, political and economic challenges in encouraging the wider and full-scale adoption of these technologies. The use of these technologies is often added into traditional packages of care, rather than replacing demand for traditional services.

What we knew already

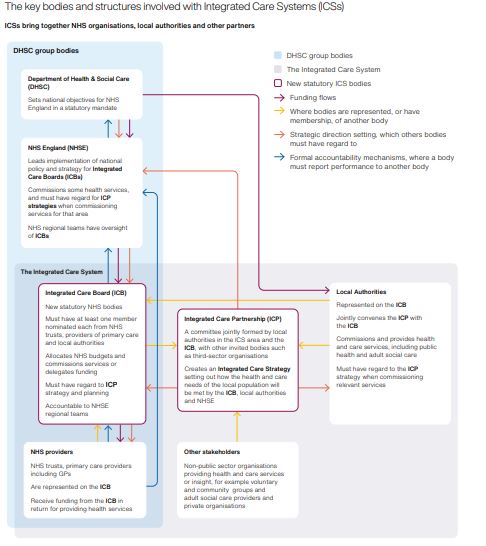

The interconnected and multi-level complexity of public sector organisations requires collaboration and consensus across different actors, both internally and externally, to ensure required outcomes are achieved. Traditional hierarchical governance models can prove ineffective in the support of the adoption of change, perhaps because bureaucratic models rely on controlling changes through a gradual process to mitigate the risk of failure – leading to creativity being stifled and the opportunity for innovation lost.

Wider adoption of technology requires more effective involvement of adult social care stakeholders. A networked governance approach might help public sector bodies to involve a wider range of actors in the defining of, and solution finding to, entrenched problems. The key characteristics of a networked approach are the bottom-up nature of decision making, collective group-led decisions and wider participation of different members that have a role in the taking forward collective action. Networked governance has the potential to unlock entrenched and complex issues through this collective approach drawing on peer to peer collaboration and action.

Public leaders can create an environment for innovation, within which actors are empowered to identify and take advantage of new opportunities, through influence on the culture and values of an organisation. With fast changing technologies and public demand for innovative and effective technological access to public services, leaders need to understand their operating environment and make decisive decisions about when and how to adopt new technologies. Leaders also have important roles in encouraging professionals and service users to adopt technology to be a replacement for traditional care services. Adaptive leadership styles can help flex the way in which challenges and problems are addressed, through the articulation of the challenge and use of different styles and contextual approaches to problem solving, enabling followers to connect with the problem and galvanising action to resolve it.

The availability of advanced technologies is helping to redefine how people receive support and tackling issues such as social isolation and workforce gaps. Technology can provide opportunities to reduce costs and to improve the quality of care and quality of life amongst users. However, public and professional attitudes and awareness towards the use of technology in care is mixed. Some citizens are unable to access and use technology due to economic issues or skills deficiencies. Some choose not to because they do not perceive sufficient positive benefits.

Successful adoption of ASC digital technologies

The research highlighted the need for care technology in the home to become part of the standard way of operating within adult social care. Many care users don’t know what care technology in the home is available, how it can be used and the associated possibilities. Behavioural approaches such as exploring capabilities, opportunity and motivation for change, positive action and encouragement can help adoption of technologies.

People need to see, and sometimes even experience, the benefits of the technology before truly getting onboard with using it. Participants highlighted opportunities for demonstrating the possibilities of care technology by using reference sites or research exemplars, where success has already been achieved.

One of the most significant barriers to digital adoption highlighted in the research relates to the skills and confidence of stakeholders to use technology. The concept of ‘digital buddies’ can help to provide peer to peer support, alongside addressing a lack of affordable digital infrastructure and connectivity in some areas. There is a role here for public leaders to ensure support is provided to reduce the risks of digital exclusion.

How leaders influence digital adoption

Leaders can play an active role in leading digital adoption, actively using and promoting the benefits of the care technology. They can develop a clear vision and narrative with partners, helping people understand what difference care technology in the home can have to the way people work and are supported to live independent lives, focussing on specific benefits and bringing the vision to life. Change can easily slip back into old working practices and so leaders need to remain committed to the change whilst adapting to changing situations.

For lasting adoption of digital technology in the home leaders need to explain how it’s a better way of working or receiving care. Leaders need to acknowledge they can’t implement the change alone and need others to develop and iterate the change, empowering staff to be creative. Leaders need to adapt to changing situations, understanding and accepting issues. Adaptive leaders understand what isn’t working and quickly adapt to change their approach, gathering insights from real users of care technology to use their perspectives to develop understanding and learning.

The effect of governance arrangements

Networks involved in digital adoption in social care need to develop strong mechanisms for dialogue to influence their work and direction, integrating awareness of the work across partnerships so that there can start to be a sense of collective ownership for the change that is being proposed.

Partnerships can help de-risk change initiatives. At the personal level, the adoption of digital approaches in the home can seem quite daunting for people and many appear reluctant to adopt digital changes in the home because they are unfamiliar with them. Through a partnership approach individuals and groups can come together to support each other to test and trial the technology, thus becoming more confident with it, working together to achieve their digital adoption goals. At the organisational level, organisations may feel reluctant to adopt new technologies and ‘be the first’, perhaps because of associated social or financial risks. By working together partnerships have the potential to reduce these risks, spreading either the financial burden or the associated social impact.

Individuals play key roles in shaping group attitudes and behaviours, by influencing as sector leaders across adult services. This influencing can often be an effective tool for encouraging others to adopt new initiatives, by either direct engagement or simply because they don’t want to be left behind. Individual service users are similarly important, one focus group member talked about how it often ‘just takes one person to show the way and the rest follow once they see the benefits’ of social care technology in the home. Working directly with users of services can improve the rates of digital adoption, ensuring that products being purchased fit the needs of users and are adopted.

The role of place level governance has the potential to influence the impact of digital adoption across networks, normalising their use and enabling users to become familiar with the available solutions, thus leading to greater adoption.

Conclusions

Digital technologies are changing the way we interact and how we live. The necessity to adopt and integrate technology has never been more critical in adult social care. This research provides insight into the challenges faced by professionals, carers and service users when embarking upon a digital change journey. It illustrates how different ways of engaging and working with stakeholders can be tried and iterated to achieve the goal of digital adoption.

The research provides several key points that should be considered when addressing the challenges of digital adoption. Firstly, the awareness of, and confidence in using, digital technologies is vital for adoption to succeed. Secondly the role of the leader in being able to own the change and empower others to shape and implement digital change is a powerful tool for supporting wider adoption. The adaptive leadership style lends itself well to being flexible and able to adjust to meet the challenges of digital adoption.

Finally, effective partnerships and networks can support digital adoption. The collaborative nature of effective partnerships enables benefits to be shared whilst reducing the risk of a single organisation undertaking a venture. The research identified the benefits of networks of service users and their carers being able to influence adoption of digital services.

_________________________________________________________________________________

About the project

This research was a Master’s dissertation as part of the MSc in Public Management and Leadership, completed by Marc Greenwood and supervised by Dr Louise Reardon. Marc can be contacted at [email protected]. The research included interviews with leaders who had led projects or service improvement activities within their own, or partner organisations, to adopt technology in adult social care; a 15-person focus group consisting of social care users and carers; and interviews with representatives of relevant network organisations.

Further information on Inlogov’s research, teaching and consultancy is available from the institute’s director, Jason Lowther, at [email protected]

Twitter @Inlogov Blog Inlogov.com