Chris Game

PoliticsHome, the online Parliamentary news source, recently commissioned a Redfield & Wilton Strategies poll into the public’s awareness and understanding of the Government’s ‘flagship’ slogan – sorry, policy – of ‘Levelling Up’.

It wasn’t great – the awareness and understanding bit, I mean, not the poll. “Somewhat” and “moderately aware” responses formed the clear majority, with a further third of respondents shamelessly admitting “no understanding at all”.

Which left 14% reckoning they were “well aware” – confident perhaps that they’d not be pressed for details. That’s one in seven potential voters claiming familiarity with the Government’s two-year-old core domestic policy. Hardly impressive, but I’m sorry – I didn’t believe this particular sub-sample of the Great British Public, even when I first read it.

That is, before the week in which we learned that none of the HS2 eastern leg, the planned Northern Powerhouse Rail, and the Government’s cap on social care costs were, as widely supposed, integral to Levelling Up

Not the least of my reasons for doubting that 14% “well aware” figure was that I’d question whether that many Conservative MPs (50+) would seriously have claimed such familiarity. Even returning from October’s annual party conference, they were openly pleading for fewer “buzzwords” and some “meat on the bones” to offer their increasingly disaffected constituents.

Hardly surprisingly, considering all they’d got from the proverbial horse’s mouth – Levelling Up Minister Neil O’Brien at a Policy Exchange fringe event – was that it’s a “four-fold concept”, involving empowering local leaders and communities, growing the private sector in areas with lower living standards, improving public services, and heightening civic pride. Just what PoliticsHome’s 14% had in mind, no doubt!

But then O’Brien got carried away, almost parroting Douglas Adams’ Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy: “It’s big – You just won’t believe how vastly, hugely, mind-bogglingly big it is. You may think it’s a long way down the road to the chemist’s, but that’s just peanuts to …”

Adams, of course, was describing space. Compare O’Brien on Levelling Up: It’s “a huge expensive thing … and will help all people who’ve long felt neglected”. And there’ll be even more “in the Levelling Up white paper we’ll be publishing … (pause for drumroll) … shortly”.

Or not so shortly, as we learned this past weekend from the DLUHC’s otherwise largely silent ‘big hitter’, Michael Gove – but quite possibly featuring “swathes of rural England [electing] powerful American-style governors”. Odd that O’Brien didn’t mention them!

Either way, it’s frustrating for all concerned, particularly with Ministers having been handing out – and some of their constituencies receiving – tranches of supposedly Levelling Up-type funding for over two years now. So many tranches, indeed, that it’s genuinely hard to keep up.

And that’s not the purpose of this blog, but even a highlights list would include:

* £3.6 billion Towns Fund – launched as effectively the new PM’s first policy initiative in July 2019, this one would “unleash the full economic potential of [eventually 101] English towns … as part of the Government’s plan to level up our regions”.

An initial 1,082 towns were narrowed down to the “most needy” 50%, then grouped regionally by “officials” into high, medium and low priority. All 40 ‘highs’ were selected for funding of up to £25m, with ministers choosing the remainder “based on the information provided and their own judgement”.

Which enabled Communities Secretary, Robert Jenrick, to judge his junior ministerial colleague Jake Berry’s 270th most deprived constituency as still pretty ‘needy’, in apparent exchange for Berry making a similar evaluation of Jenrick’s Newark.

* UK £220 million Community Renewal Fund – awards to help 100 particularly needy places/communities across the UK prepare for next year’s launch of the (very much bigger – est. £1.5 billion) UK Shared Prosperity Fund that will replace EU structural and investment funding.

Bids were ranked on five ‘metrics’ – productivity, skills, unemployment rate, population density, and household income – with final funding decisions made by the Secretary of State for the (now) Levelling Up, Housing and Communities Department, “after considering any comments from ministerial colleagues”. No actual mention back then of Levelling Up, and disgruntled moans this time from MPs and councils across the spectrum – but, with over £15m to Moseley Road Baths, it wasn’t all bad.

* £4.8 billion Levelling Up Fund – this one is definitely about Levelling Up, bringing together that department, the Treasury, and Transport to invest in “high-value local infrastructure”. Focus is on “places where it can make the biggest difference to everyday life, including ex-industrial areas, deprived towns and coastal communities”.

Come the results, though, we were back in Towns Fund territory – Sajid Javid’s Bromsgrove constituency and Culture Secretary Nadine Dorries’ Central Bedfordshire being levelled up still further from their positions among the least deprived fifth of authorities nationwide.

As with most of these exercises, the assessment process and criteria are explicit, but without providing the key information successful or, even more, unsuccessful bidders really want. There are “pass/fail gateway criteria”, assessment criteria – here covering “strategic fit, deliverability, value for money, and characteristics of place” – giving GB bids a potential score of 100. Following which, Ministers are increasingly involved, together with and guided by officials (of course), but in an essentially indeterminable way.

MPs, naturally, react at least in the first instance to whether ‘their’ patch has ‘won’ or ‘lost’ in these funding contests. Not so the Commons Public Accounts Committee – Labour-chaired, but Conservative-dominated – who, pretty well from the outset with the Towns Fund, have criticised severely the blatant Ministerial involvement in the “not impartial” selection process.

Civil servants had ranked towns into three categories by local need and growth potential, then chosen all 40 ‘High Priority’ ones. Whereupon Ministers then selected a further 60, heavily represented by Conservative MPs, from the Medium and Low priority categories. Twelve Low Priority areas won out over Medium Priority towns, including Greater Manchester’s Cheadle, ranked 535th out of 541, but with a vulnerable 2,336 Conservative majority.

“Vague and based on sweeping assumptions” was the Committee’s verdict on Ministers’ selections, which risked jeopardising the civil service’s reputation for integrity and impartiality.

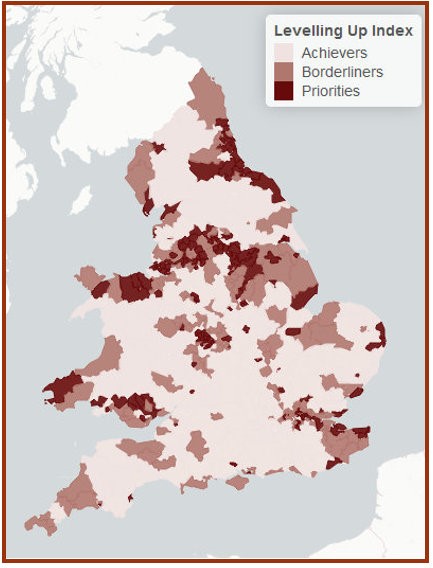

With something at least as sophisticated and certainly more objective evidently required, up stepped WPI (Westminster Policy Institute) with its Levelling Up Index. It attempts almost exactly what the Government claims it wants: a comprehensive socio-economic statistically based identification of those areas (though by parliamentary constituency, rather than local authority) most in need of levelling up.

WPI’s Index assigns all English and Welsh constituencies ‘Levelling Up’ rankings – from the most needy, Blackpool South (1), to the least, South Cambridgeshire (573) – then divides them into three categories: Priorities, Borderliners, Achievers.

Achievers, mainly in the South and upwardly mobile suburbs of major urban centres, perform better than Borderliners, who constitute the national average and are judged to require support in certain areas. Levelling Up Priorities, though, should be places, disproportionately in the North, Midlands, and Wales, that have historically suffered through industrial decline, and often additionally through Government spending policies.

Six indicators combine to determine a Levelling Up score: spending power; financial dependency, based on Job Seekers’ Allowance and Universal Credit claims; crime rates; deprivation scores; health measures; and empty commercial properties.

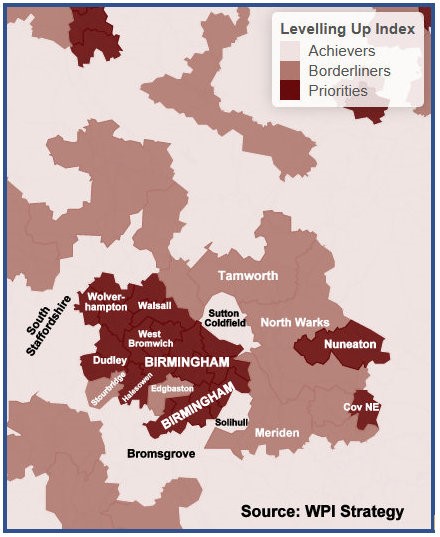

Better still, there’s an excellent interactive WPI Index Map, the enlarged West Midlands section of which shows clearly the prioritisation the six indicators suggest our region’s constituencies should be accorded in any objectively conducted Levelling Up exercise.

The map’s core message barely needs commentary, but some individual Levelling Up scores are useful. The whole metropolitan West Midlands is a Priority, with the exceptions of Borderliners Edgbaston (sounds familiar – 208) and Stourbridge (210), and Achievers Sutton Coldfield (452) and Solihull (524).

Other Birmingham scores range from Erdington, Ladywood, and Hodge Hill (9, 10 15), through Perry Barr, Hall Green, Yardley, and Northfield (43, 55, 60, 62), to Selly Oak (156).

Viewed pictorially, we look pretty determined to get our deserved recognition. To me, anyway, we resemble a rather ferocious, albeit three-legged, tail-docked Cockapoo – about to attack those South Staffs Achievers, before making mincemeat of Boris’s Peppa Pig.

Chris Game is an INLOGOV Associate, and Visiting Professor at Kwansei Gakuin University, Osaka, Japan. He is joint-author (with Professor David Wilson) of the successive editions of Local Government in the United Kingdom, and a regular columnist for The Birmingham Post.