Chris Game

They’ve become a standard feature of the election season – complaints about the complete or partial closure of schools selected as polling stations. Some, no doubt, are from the actual children whose education is being potentially disrupted. But more come from heads of affected schools – who are informed, rather than requested, by their respective council Returning Officers, and feel they have little say, even over any financial reimbursement – and from teachers, who have no leave entitlement but are expected somehow to make up lost teaching time.

Bitterest protesters, though, are understandably working parents. Facing fines if they decide to take their children out of school for a day, even for something educational, they’re told by, in effect, their Local Education Authority that in this case they must do so, and no, on this occasion it’s really not detrimental to their child’s learning. Plus, they must find and pay for responsible childcare at pretty short notice.

This year was less irksome than those when polling day is in Bank Holiday week itself, but for many it was still pretty unsettling: close on Thursday, reopen Friday, close on Monday, reopen Tuesday. And last year, of course, we had Theresa May’s ‘snap’ General Election in early June, called too late to combine with the locals, thereby doubling the grief for many.

But for how many? Difficult, because in our localised ‘system’ of electoral administration, no one really knows. Local authorities select the buildings they’ll use as polling places, and the Electoral Commission keeps no collated records. All we actually know is that it differs from council to council – greatly, as was illustrated by one of this year’s complainants – the independent campaigning group Parents Outloud, as reported in the London Evening Standard.

Even the group’s non-systematic comparison of London borough polling arrangements showed that practices varied widely. “In Tower Hamlets, 43 school buildings were turned into polling stations, in Croydon 33, Kensington & Chelsea 18, Kingston upon Thames seven … and in Camden four schools closed.”

“Turned into” obviously isn’t the same as “closed”, but it seemed clear Camden’s approach differed markedly from that of at least some of those other boroughs. And a check of the council’s complete list of 60 polling stations showed just five schools in total, or 8%. The other 55 were community centres, council buildings, church halls and other religious venues, libraries, gymnasia, and, pleasingly, The Pirate Castle – which isn’t in this case a pub, but a children’s water sports centre on the Grand Union Canal. Either way, though, it and Camden’s other 54 polling stations wouldn’t have involved children missing a day’s school and parents having to find child care.

I don’t know if it’s an actual Camden policy to avoid using schools where possible, and ignore the Electoral Commission’s guidelines positively pushing schools as an easy and financially advantageous option:

“Schools that are publicly-funded, including academies and free schools, may be used as polling stations free of charge, and the legislation allows Returning Officers to require a room in such schools for use as a polling station.”

But I once did some work for the 2007 Councillors Commission, chaired by Dame Jane Roberts, a former Leader of Camden Council and also a Child Psychiatrist, and I’d be surprised if it’s accidental.

It also prompted me to check Birmingham’s list of polling places, particularly as journalist Anna Tobin had done a detailed count of all 460 in 2014, finding that 60% were in schools, whereas for Leeds’ 357 it was only a quarter. As she acknowledged, from a Returning Officer’s perspective, schools tick all the boxes: general accessibility, disabled access, available parking, facilities for polling station staff, and above all free to hire. In short, the almost too easy option. There’s little doubt local authorities could be a lot more imaginative, if they chose, and examples are cited, like Cambridge City Council, that manage simply not to use schools as polling stations.

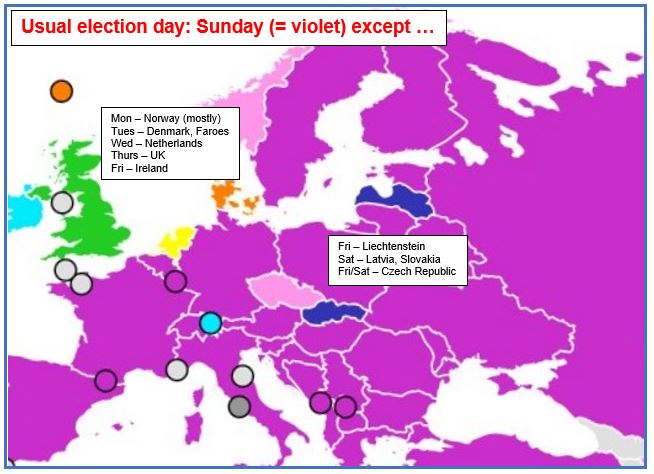

Beyond that, one’s instinctive solutions depend a bit on perspective. Parents Outloud are clear that, if councils can’t or won’t find alternatives to schools, then one or the other should provide free childcare. To which I’m extremely sympathetic, but I’m not and never have been a parent. My own preferred solution, therefore, would be to do what the great majority of countries do and hold elections at the weekend – whether on Sunday, which most do, or Saturday, or even both doesn’t particularly bother me.

I used to have a map of countries’ usual election days, which at a push – including explanations of why, say, Americans always vote on the first Tuesday after November 1st, and the Irish, as in this month’s abortion referendum, on Fridays – could be spun into a whole lecture.

My received understanding of our post-1918 choice of Thursdays, incidentally, was that it was the day furthest from either pay-day Friday, when voters might be unduly grateful to Conservative brewers, or Sunday, when more Liberal-inclined Free Church clergymen could get at them.

The last Labour Government, curious as to whether weekend voting might reinvigorate the democratic process, and – who knows? – maybe get more potential party supporters into polling stations, issued a consultation paper on Weekend Voting almost exactly ten years ago. The evidence was mildly positive. Among responding members of the public, a small majority supported weekend voting, and in an Ipsos MORI survey (p.22) 36% of self-identified non-voters said they’d be more likely to vote at the weekend, with just 2% saying they’d be less likely to.

Unsurprisingly, like so many constitutional reform initiatives, this one came to nothing, and, with weekend voting being such an obviously entrenched Euro-practice, it’s not about to be resuscitated any time soon. Personally, therefore, I’m getting behind Parents Outloud: free childcare or, better still, the ears of some sympathetic Returning Officers.

Chris Game is a Visiting Lecturer at INLOGOV interested in the politics of local government; local elections, electoral reform and other electoral behaviour; party politics; political leadership and management; member-officer relations; central-local relations; use of consumer and opinion research in local government; the modernisation agenda and the implementation of executive local government.

Chris Game is a Visiting Lecturer at INLOGOV interested in the politics of local government; local elections, electoral reform and other electoral behaviour; party politics; political leadership and management; member-officer relations; central-local relations; use of consumer and opinion research in local government; the modernisation agenda and the implementation of executive local government.

All views expressed in this blog are those of the author and not of INLOGOV or the University of Birmingham.