Chris Game

As Lady Bracknell would certainly not have observed: to overlook the UK’s first serious exercise in gender pay gap reporting may be regarded as a misfortune; to overlook additionally the near coincidence of America’s Equal Pay Day would look like literal carelessness. So we won’t.

Butchering another clichéd quotation, last week’s historic publication by nearly 10,000 companies and public sector organisations of broadly comparable gender pay gap data could be loosely likened to Churchill’s characterisation of the war-turning battle of El Alamein in November 1942: “not the end; not even the beginning of the end, but perhaps the end of the beginning.”

In this instance, an even more protracted beginning. And indeed, there is a figure of Churchillian admirability in the equal pay battle too – a remarkable woman politician, though certainly not Theresa May, despite her audacious attempts to persuade us otherwise last weekend.

Yes, it was Prime Minister May who did eventually introduce Statutory Instrument No.172 (2017) – the Equality Act (2010) (Gender Pay Gap Information) Regulations – with its key ‘duty to publish’ stipulations: gender pay gaps, proportions of men and women by salary quartile, bonus payments, and, arguably most important of all, to do so annually.

But it was also Home Secretary May, the new Conservative-led Coalition and its business supporters who were responsible for delaying this beginning by the seven years between those two bracketed legislative dates, by doing their utmost in 2010 to dilute the implementation of the genuinely radical Equality Act inherited from the Labour Government and its author and driver, Equalities Minister Harriet Harman.

Positive Action just survived – enabling an employer, faced with two candidates of equal merit, to recruit or promote one from an age, racial or gender group under-represented in the workforce in order to increase its diversity. But not the pivotal gender pay audit – “Theresa May axes Harman’s Law”, as the Telegraph exulted. Instead of employers having to reveal their gender pay gaps, a voluntary approach, we were assured, would be preferable. And true, some big companies did respond: five, to be precise.

So, by 2015, with the UK’s overall gender pay gap – that is, between the total pay averages of all, not just full-time, workers – still close to 20%, it was clear even to ministers that voluntary wasn’t working. Compulsory annual reporting, gender pay gap league tables, and annual gap-closing targets are no magic wand. But they furnish authoritative and hard-to-deny data, and highlight details, patterns and trends – the virtual absence, for instance, of a gender pay gap for full-time men and women between 22 and 39. They also indicate where further data are needed and enable genuinely informed debate.

Hence, the end of the beginning. Harman had been right, although her Equality Act would have constituted a much bigger, as well as earlier, beginning. For, despite its interminable gestation, this month’s exercise has major limitations. First, it is confined to organisations with 250 or more employees – a count which, contrary to some reports, should include part-time workers and job-sharers (as whole employees), but, significantly for councils, not agency workers or service companies.

Secondly, there is no definitive database of companies with 250-plus employees. No way of knowing, therefore, who’s not reported, never mind penalising them for non-compliance. The most the Government Equalities Office (GEO) can threaten is that non-compliance runs a “reputational risk”. Scary! Thirdly, there’s no way, with only 14 pieces of information requested, of checking patently implausible returns – not even overall employee totals by gender.

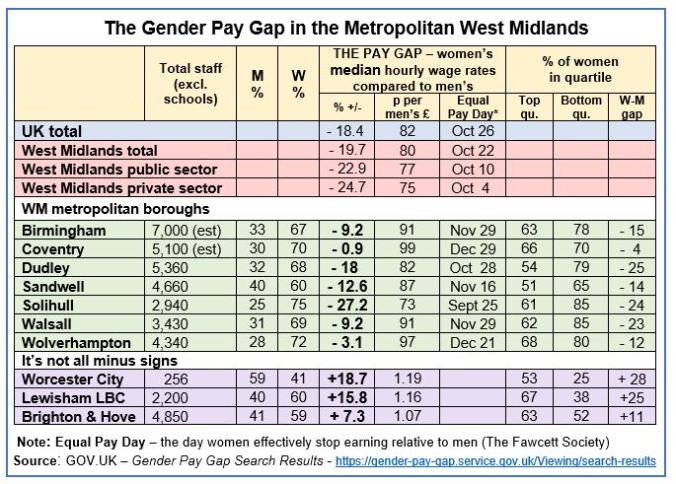

For illustrative purposes, I’ve made my own small comparison of West Midlands metropolitan councils’ returns – obviously very limited in scale, though slightly more than a straight lift from the GEO website.

The 14 items of information required of employers comprised:

1 – 2: Mean gender pay gap – difference between women’s and men’s average hourly wage rates across the whole organisation, a -10% gap meaning women’s hourly wage is 10% lower than men’s and that they earn 90p for every £1 that men earn.

3 – 4: Median pay gap – calculated by ranking all employees from highest paid to lowest paid and taking the hourly wage of the person in the middle, a -10% gap meaning the middle-paid woman’s hourly wage is 10% lower than the middle-paid man’s. Median pay is widely considered the preferable measure of ‘typical pay’, less influenced by workers with either very low or very high pay, and is the measure used here. Currently it is 18.4% for all workers, 1% higher than the mean pay gap.

The GEO helpfully translate the percentages into more readily graspable cash terms, but I’ve always liked the US concept of Equal Pay Day, marking how far into the next calendar year the average American woman must work to earn what the average man earned the previous year – which for 2017/18 just happened to be the Tuesday of this past week, April 10th, representing a mean pay gap of about 21%.

The UK’s Fawcett Society defines it slightly differently, as the day – November 10th last year – after which women in effect begin to work for free, due to the pay gap. That column’s calculations, therefore, are mine.

5 – 9: Proportions of women in each pay quartile, calculated by dividing all employees into four even groups according to their pay, and indicating women’s representation at different levels of the organisation.

10 – 14: Proportion of men and women receiving bonuses; mean and median gender bonus gaps. Important statistics, but excluded here, since Solihull and Walsall were the only councils paying bonuses.

Hopefully, after that much explanation, the figures speak largely for themselves, at least as a starting point for discussion or further examination. The sector headline results were widely reported, particularly by the Local Government Chronicle, though usually using mean, rather than median, figures. Two-thirds of councils – 193 of 293, and all but Coventry in the WM metro sample – reported mean pay differences of over 5%, the threshold deemed “significant” by the Equality & Human Rights Commission. In just 18 of the 193 cases was the gap in favour of women, but these did include both Worcester City and neighbouring Wyre Forest councils.

The former, interestingly, is fractionally over the 250-employee threshold, but obviously plenty of smaller districts are below, like Malvern Hills (in which an INLOGOV colleague has more than a passing interest), which shares an all-male senior management team with Wychavon district, but the genders of whose 170 staff it’s not required even to count. Not yet, anyway. But, as Harriet Harman would be entitled to note, this is barely the end of the beginning.

Chris Game is a Visiting Lecturer at INLOGOV interested in the politics of local government; local elections, electoral reform and other electoral behaviour; party politics; political leadership and management; member-officer relations; central-local relations; use of consumer and opinion research in local government; the modernisation agenda and the implementation of executive local government.

Chris Game is a Visiting Lecturer at INLOGOV interested in the politics of local government; local elections, electoral reform and other electoral behaviour; party politics; political leadership and management; member-officer relations; central-local relations; use of consumer and opinion research in local government; the modernisation agenda and the implementation of executive local government.

This blog was originally posted on the Political Studies Association Insights blog.

The views and content of this blog reflect the views of the author and not the views of INLOGOV or the University of Birmingham.