Chris Game

We all know why the English local elections on 5th May are important, don’t we? They’ll test Labour’s electability under Jeremy Corbyn, and possibly Corbyn’s own survivability. They’ll show whether the Lib Dems’ glacially slow recovery has been boosted by their new leader, Tim Farron – and whether UKIP repeats its General Election performance in votes (lots) or seats (very few). Above all, though, the parties’ national equivalent vote shares will be taken as an early indicator of who might win the 2020 General Election – by the people who last year couldn’t on 6th May tell us who would win outright the following day.

To be fair, that these elections are actually about thousands of candidates fighting to win nearly 2,750 seats and thereby influence the policies of over a third of the nation’s councils, including many of the biggest and financially hardest hit, usually does get mentioned somewhere in the media election previews. But the numbers are so big, and all the different council types and electoral systems so head-hurtingly complicated, that speculating about Corbyn and 2020 is just much easier.

What’s even sadder is that in some ways they’re right. For a small, non-federal country, with barely 400 principal councils rather than the 8,000+ of other EU countries our size, and already some of the lowest levels of interest and participation in local government, we do erect ludicrous hurdles of added complication for anyone wondering whether or not they’ve actually got a vote this time round.

So I reckon that’s what local election previews, certainly in these columns, should be chiefly about – treating them as the local government contests they are, and steering a way through the clutter. I’m not sure at this stage how many previews there might be, but this first one’s the stage-setter, with x later ones looking in more depth at some of the key contests.

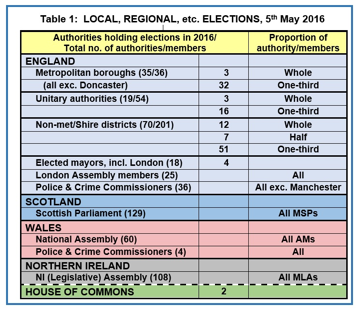

Table 1 sets out the whole show: all the UK elections taking place on 5th May – even, as an ‘etc.’, the two parliamentary by-elections in Ogmore and Sheffield Brightside & Hillsborough. The previews, though, will focus very largely on the English locals – partly because they involve far more voters than all the rest put together, and partly because, as the necessity of the table’s middle column table indicates, they offer more than enough to deal with.

About the only clear, consistent feature of our local electoral system is that all councillors normally serve four-year terms of office. Pretty well everything else, as the Electoral Commission has for years patiently noted and sought to have simplified, is unclear, inconsistent, disjointed, democratically discriminatory, and inevitably publicly bewildering.

Metropolitan boroughs

This year, for instance, although London borough councils are elected in whole-council elections every four years (2014, 2018), their metropolitan borough equivalents have until very recently all been elected by thirds in three years out of four. 2016 is, as it happens, Year 3 in the cycle – Year 4 being when we’d be electing the metropolitan county councils, had they not been abolished three decades ago.

32 of the 36 met boroughs, therefore, will be electing one-third of their councillors, as normal. Doncaster won’t be electing any, as one consequence of having from 2010 to 2014 been placed by Communities Secretary Eric Pickles under ‘statutory corporate governance intervention’, following an independent inspection report that raised serious concerns about the council’s governance in general and its management of children’s services in particular.

With children’s services transferred to a completely new body, the Doncaster Children’s Services Trust, Pickles ordered the Local Government Boundary Commission for England (LGBCE) to conduct an electoral review of the council. The review ruled that the council be reduced from 63 members to 55, that the new council be elected in May 2015 for a two-year term of office, and from 2017 in four-yearly whole-council elections running alongside the mayoral election.

The LGBCE’s final 55-member total no doubt took account of Doncaster’s being an elected mayoral authority. However, both the reduction in councillor numbers and the move to whole-council elections are becoming trends, as evidenced in our own Birmingham City Council. Following the attentions of an Independent Improvement Panel – a diluted version of Doncaster’s statutory intervention – the LGBCE has proposed that it cut its size from 120 to 101 councillors, representing (somehow) an average of nearly 11,000 residents each, with four-yearly whole-council elections starting in 2018.

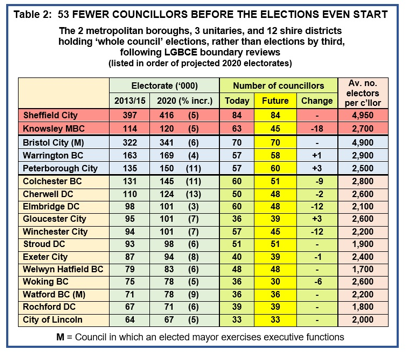

As the title and content of Table 2 suggest, though, the ever-fewer-councillors trend is observable not just in the LGBCE’s ‘punitive’ electoral reviews, but also in the far greater number prompted by a concern to improve levels of electoral equality for local voters within individual authorities. The emphasis is important, because, as can be seen from the table’s list of all the councils whose electoral cycles, like Doncaster’s, have been affected this year by boundary reviews, the LGBCE consider any comparison of electorate size across similar or even (Gloucester and Stroud) adjacent councils as an irrelevance to electoral equality.

Thus – as shown in the table in the preceding link – Doncaster’s 222,000 electors are judged to be appropriately served in future by a council smaller than those of 13 met boroughs with electorates of under 200,000, and 30% (23 councillors) smaller than Newcastle’s 202,000 electors are felt to need or deserve. Again for no explained reason, Sheffield’s now confirmed 84 councillors will each have to represent nearly a thousand more electors than their counterparts in Manchester (96 councillors), Bradford and Liverpool (both 90).

Also noteworthy in these boundary reviews is that, even though the electorates in every council in the table are projected to increase by 2020, the attainment of the desirable degree of equality seems much more frequently to require a cut in the number of councillors than an increase – presumably on the reasoning that, for something purporting to be local government, ward electorates are already so large that another few hundred won’t make much difference.

Returning to Table 1, the third met borough holding whole-council elections – in addition to Knowsley and Sheffield – is Rotherham. This is another ‘punitive’ measure, following the 2015 findings of the Jay and Casey reports that the council was still in denial about the extent of child sex exploitation in the town, and a team of commissioners taking over, in this instance for potentially four years, many of the council’s functions. As part of this unprecedentedly comprehensive intervention package, Communities Secretary Pickles ruled that, starting in 2016, all councillors should face re-election and the whole council move henceforward to four-yearly whole-council elections.

Unitary authorities

This is where the complications really start, because ‘unitaries’ may be either unitary counties (UCs) or districts (UDs). UCs have no choice but to adopt counties’ four-yearly cycle (2013, 2017). UDs may choose a four-yearly cycle (2011, 2015, 2019), and most do, but they also have the by-thirds option open to shire districts (2012, 2014, 2015, 2016). This year, though, in addition to this latter group, there are three unitaries with whole-council elections following boundary reviews: Peterborough, Warrington and Bristol. The latter two are switching permanently to a four-yearly cycle, in Bristol’s case coinciding with the mayoral election – of which there will be more in subsequent blogs.

Shire districts

As can be deduced from Table 1, the 201 shire district councils luxuriate in not just two electoral cycle options, but three: whole-council elections, by thirds, or by halves (2014, 2016, 2018). Only seven avail themselves of this last arrangement, and, with 2015 being the big whole-council year, most councils up this year are those which elect by thirds, including 12 which, following full-scale boundary reviews, are electing whole new councils, several of which will be notably smaller than before.

If you’ve reached this far, congratulations! Ensuing election blogs will, I promise, focus entirely on contests: no more procedures, but parties, participants, policies, and possible outcomes. My point, though, would be that, if procedures have got in the way of this blog, they similarly get in the way of voters’ understanding and therefore turnout. The Electoral Commission, in the critical report referred to earlier, concluded that:

“a pattern of whole council elections for all local authorities in England would provide a clear, equitable and easy to understand electoral process that would best serve the interests of local government electors. The Commission recommends that each local authority in England should hold whole council elections, with all councillors elected simultaneously, once every four years”.

At present, this appears to be the model imposed by ministers on individual ‘naughty’ authorities. Wouldn’t it be preferable, in the interests of public understanding, interest and participation, and possibly even of councils themselves, to embrace the Commission’s idea and give ourselves the chance, if we chose, to ‘vote all the rascals out’ on a single ‘Local Elections Day’? Bearing in mind all the myriad discretions our local authorities don’t have, this electoral cycle option is surely one they could live without.

Chris Game is a Visiting Lecturer at INLOGOV interested in the politics of local government; local elections, electoral reform and other electoral behaviour; party politics; political leadership and management; member-officer relations; central-local relations; use of consumer and opinion research in local government; the modernisation agenda and the implementation of executive local government.